After a year largely spent doing other things, it was a pleasure to return to the Bradford area this weekend to reprise my ongoing, water-themed double-act with singer-songwriter Eddie Lawler at not one but two local festivals. In the end, I think it’s fair to say that our Sunday gig (September 9th) was more enjoyable than Saturday’s — but ironically enough that’s mainly because of water… On Saturday (8th) it was pouring down out of the sky with enough force and frequency to, er, dampen anyone’s fun…

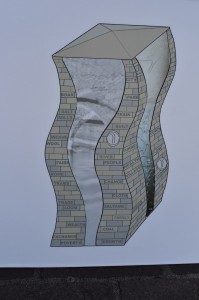

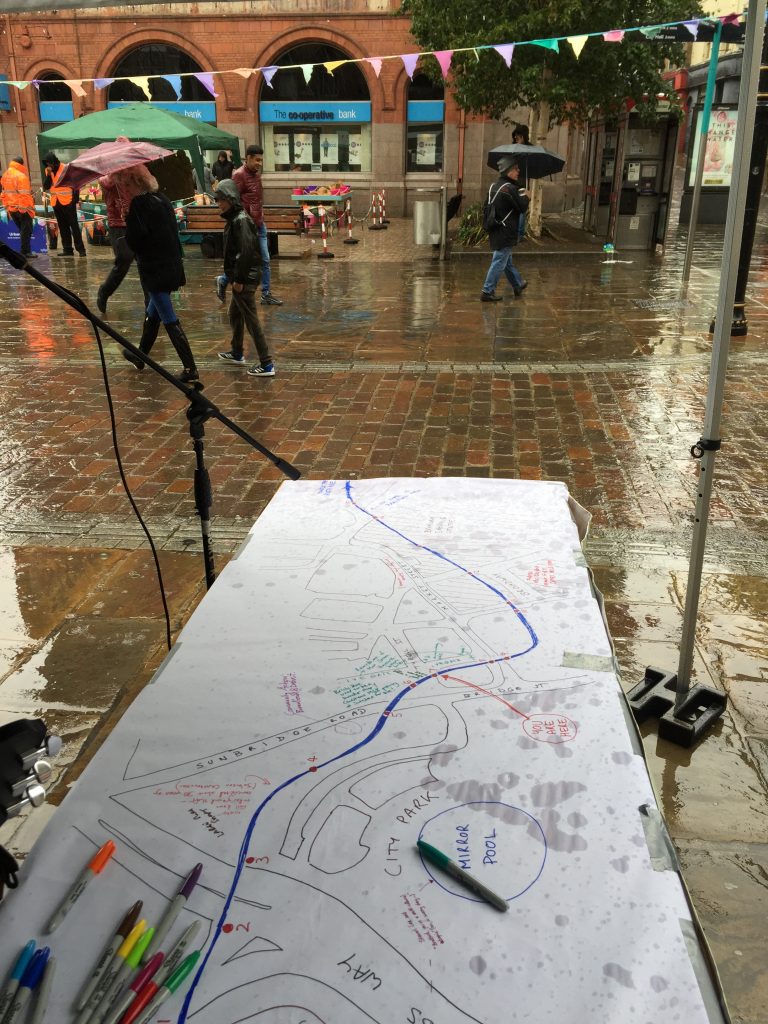

This was my vantage point on Tyrell Street for much of the afternoon. Eddie and I were supposed to be singing songs and telling tales of Bradford Beck, as part of the weekend’s Bubble Up festival — a water-themed arts extravaganza which had events dotted all around Bradford’s city centre. I was also attempting a bit of story-gathering as well as telling, by using a hand-drawn map of the city centre — showing the Beck’s hidden journey under its streets — and inviting passers-by to add their own annotations about memories of city centre locations. The memories added went as far back as 1968, but the map didn’t get nearly as populated with text as I had hoped, because (as the picture tells you) the footfall from shoppers was poor and getting poorer all afternoon — even as the rain poured and kept pouring…

Here’s Eddie, smiling as ever, and undaunted by the weather, even though there wasn’t — in the end — much meaningful opportunity for him to use that microphone to sing. He’s huddled under the Friends of Bradford’s Becks’ portable gazebo, along with fellow Friend Elizabeth, who was timetabled to lead walks along the route of the Beck through the city centre — via the plaques that are now placed in the pavements at key intervals.

Here’s Eddie, smiling as ever, and undaunted by the weather, even though there wasn’t — in the end — much meaningful opportunity for him to use that microphone to sing. He’s huddled under the Friends of Bradford’s Becks’ portable gazebo, along with fellow Friend Elizabeth, who was timetabled to lead walks along the route of the Beck through the city centre — via the plaques that are now placed in the pavements at key intervals.

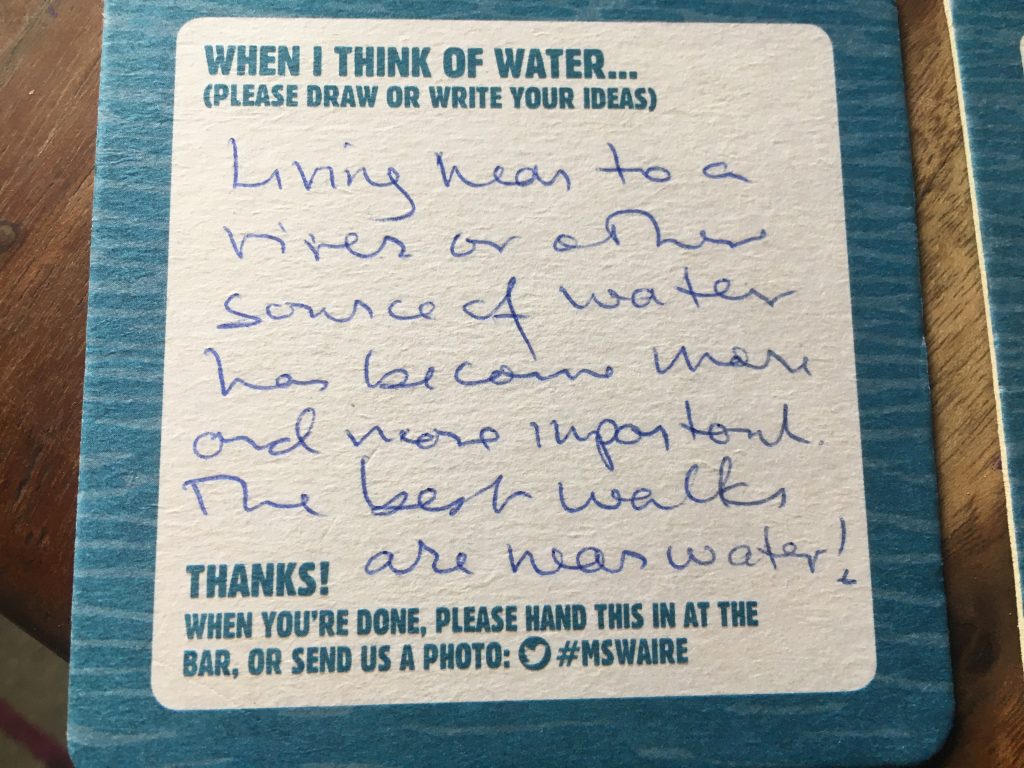

Just past the gazebo, FoBB had opened up a manhole cover and surrounded it with a safety fence — as well as a polystyrene mock-up of a slate sculpture by Alex Blakey that’s being planned as a permanent feature… By looking down the hole, you can see Bradford Beck streaming by beneath the street. Although only the most educated observer would be able to distinguish the beck from a storm drain, passers-by were nevertheless intrigued when told that this was the hidden river around which the city was first built….

Just past the gazebo, FoBB had opened up a manhole cover and surrounded it with a safety fence — as well as a polystyrene mock-up of a slate sculpture by Alex Blakey that’s being planned as a permanent feature… By looking down the hole, you can see Bradford Beck streaming by beneath the street. Although only the most educated observer would be able to distinguish the beck from a storm drain, passers-by were nevertheless intrigued when told that this was the hidden river around which the city was first built….

Across the street in Bradford’s City Park area, there were more under-trafficked gazebos and marquees, including the one from which Bradford Community Broadcasting (BCB) was live-casting for the day. Eddie and I took time out from our stall location to speak with host Mary Dowson — who was as engaging and on-the-ball as ever — about how and why we both got involved in using the arts to talk about water.

Across the street in Bradford’s City Park area, there were more under-trafficked gazebos and marquees, including the one from which Bradford Community Broadcasting (BCB) was live-casting for the day. Eddie and I took time out from our stall location to speak with host Mary Dowson — who was as engaging and on-the-ball as ever — about how and why we both got involved in using the arts to talk about water.

It was actually really interesting to talk with Mary immediately after she’d interviewed David Clapham (below, left). David is a scientist and water specialist who used to work with Bradford Council: he was really excellent at talking about the material and dynamic properties of water, in an engaging rather than a “dry” way (sorry). Eddie and I were then able to follow up from the cultural point of view, by talking not about “water” singular but about “waters” plural — as they were traditionally thought of, in the days before H2O was seen as a unified resource. (Of course waters still do vary in property and character from place to place, depending on mineral qualities etc.) Eddie’s songs often give particular watercourses personal identities, by singing in the first person: “My name is Bradford Beck… If you’re wondering what the heck I’m doing singing this song, it’s cos I have to roll along, incognito… Beneath the city streets, with no credibility…”

It was actually really interesting to talk with Mary immediately after she’d interviewed David Clapham (below, left). David is a scientist and water specialist who used to work with Bradford Council: he was really excellent at talking about the material and dynamic properties of water, in an engaging rather than a “dry” way (sorry). Eddie and I were then able to follow up from the cultural point of view, by talking not about “water” singular but about “waters” plural — as they were traditionally thought of, in the days before H2O was seen as a unified resource. (Of course waters still do vary in property and character from place to place, depending on mineral qualities etc.) Eddie’s songs often give particular watercourses personal identities, by singing in the first person: “My name is Bradford Beck… If you’re wondering what the heck I’m doing singing this song, it’s cos I have to roll along, incognito… Beneath the city streets, with no credibility…”

Alas, as you can see from this shot, our time in the BCB tent coincided with one of the heaviest of the afternoon’s downpours, which left City Park itself pretty much deserted. I do hope this wasn’t too disappointing for Bubble Up’s organisers, from the Brick Box community arts organisation. Some of the Brick Box team were there, in the BCB tent, in their distinctive water-themed wigs, trying to make the best of the situation…

Alas, as you can see from this shot, our time in the BCB tent coincided with one of the heaviest of the afternoon’s downpours, which left City Park itself pretty much deserted. I do hope this wasn’t too disappointing for Bubble Up’s organisers, from the Brick Box community arts organisation. Some of the Brick Box team were there, in the BCB tent, in their distinctive water-themed wigs, trying to make the best of the situation…  The weather was generally a lot better on Sunday (yesterday) than Saturday, so I do hope Bubble Up bubbled a bit better with some sunshine… By then, though, Eddie and I were off on our other festival weekend mission. presenting a musical walking tour for Saltaire Festival, titled The Ballad of Little Beck.

The weather was generally a lot better on Sunday (yesterday) than Saturday, so I do hope Bubble Up bubbled a bit better with some sunshine… By then, though, Eddie and I were off on our other festival weekend mission. presenting a musical walking tour for Saltaire Festival, titled The Ballad of Little Beck.

This was Roberts Park, in Saltaire, shortly before 12 noon, with the sun very much shining. Starting at the park’s bandstand, Eddie and I welcomed an audience of 15 or 20 intrepid walkers, who had come along to journey with us along long watercourses towards the ruins of Milner Field mansion — the “lost” country home of Titus Salt Jr.

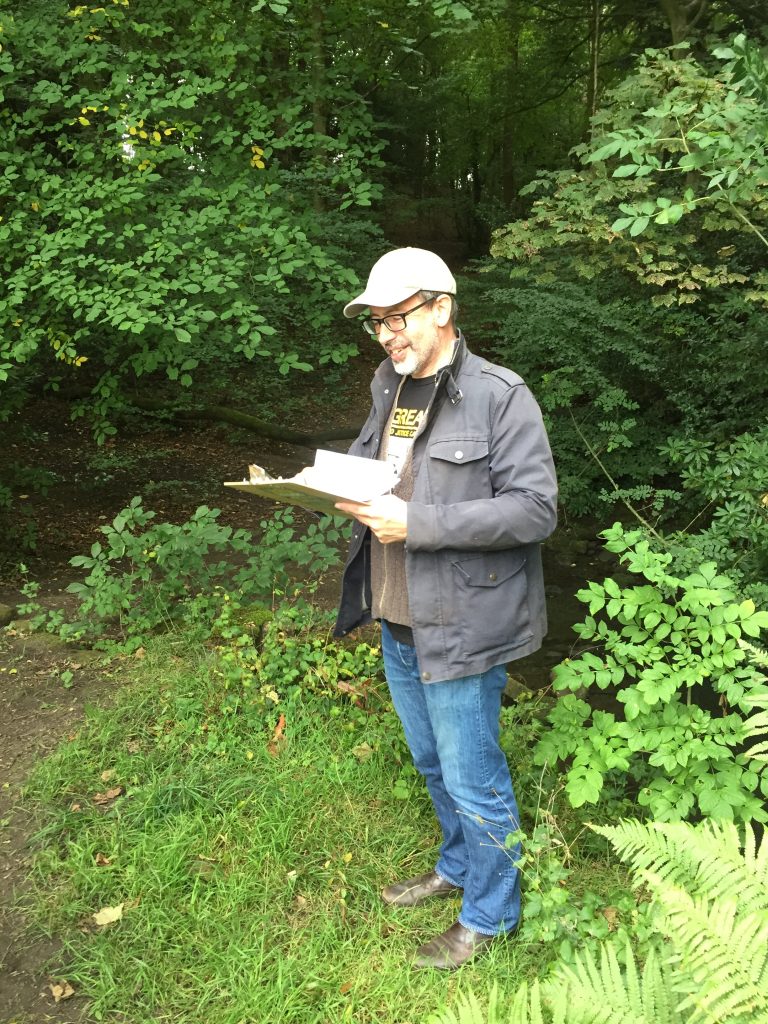

The walk was in some ways a “live remix” of parts of the Salt’s Waters audio tour (still available for download!) that Eddie and I made the other year. Our title, The Ballad of Little Beck, came from the song of the same name that Eddie wrote for the audio guide, and which tells the story of the Milner Field mansion from the point of view of the small brook that flows through the grounds and was once dammed by the Salts to make a boating lake (again: river songs in the first person!). But the balladeering theme was taken in a different direction for this new walk, as we performed a selection of poems along the way, by local poets of the Salts’ era. In the picture above, Eddie is singing — to a tune of his own devising — the poem “Come to Thy Granny” by dialect poet Ben Preston, who built the Glen pub in Eldwick. We didn’t go quite as far as Eldwick (that would have been a long walk), but instead performed this on the path towards Eldwick, just before we turned off in another direction.

The walk was in some ways a “live remix” of parts of the Salt’s Waters audio tour (still available for download!) that Eddie and I made the other year. Our title, The Ballad of Little Beck, came from the song of the same name that Eddie wrote for the audio guide, and which tells the story of the Milner Field mansion from the point of view of the small brook that flows through the grounds and was once dammed by the Salts to make a boating lake (again: river songs in the first person!). But the balladeering theme was taken in a different direction for this new walk, as we performed a selection of poems along the way, by local poets of the Salts’ era. In the picture above, Eddie is singing — to a tune of his own devising — the poem “Come to Thy Granny” by dialect poet Ben Preston, who built the Glen pub in Eldwick. We didn’t go quite as far as Eldwick (that would have been a long walk), but instead performed this on the path towards Eldwick, just before we turned off in another direction.

A little further along the route, here I am performing John Nicholson’s poem “Bingley’s Beauties”. (Thanks to Ruth Bartlett for these pics, by the way.) Nicholson was a mill worker and poet apparently loved by Titus Salt Sr., but he died in 1843, before Saltaire itself was built, when he drowned while crossing the River Aire en route to visit his aunt in, yes, Eldwick (we had traced his steps in this direction from Saltaire). As you can see from the picture below, at this point we were standing directly over Little Beck itself — halfway along Sparable Lane, heading towards Gilstead (in the parish of Bingley).

A little further along the route, here I am performing John Nicholson’s poem “Bingley’s Beauties”. (Thanks to Ruth Bartlett for these pics, by the way.) Nicholson was a mill worker and poet apparently loved by Titus Salt Sr., but he died in 1843, before Saltaire itself was built, when he drowned while crossing the River Aire en route to visit his aunt in, yes, Eldwick (we had traced his steps in this direction from Saltaire). As you can see from the picture below, at this point we were standing directly over Little Beck itself — halfway along Sparable Lane, heading towards Gilstead (in the parish of Bingley).

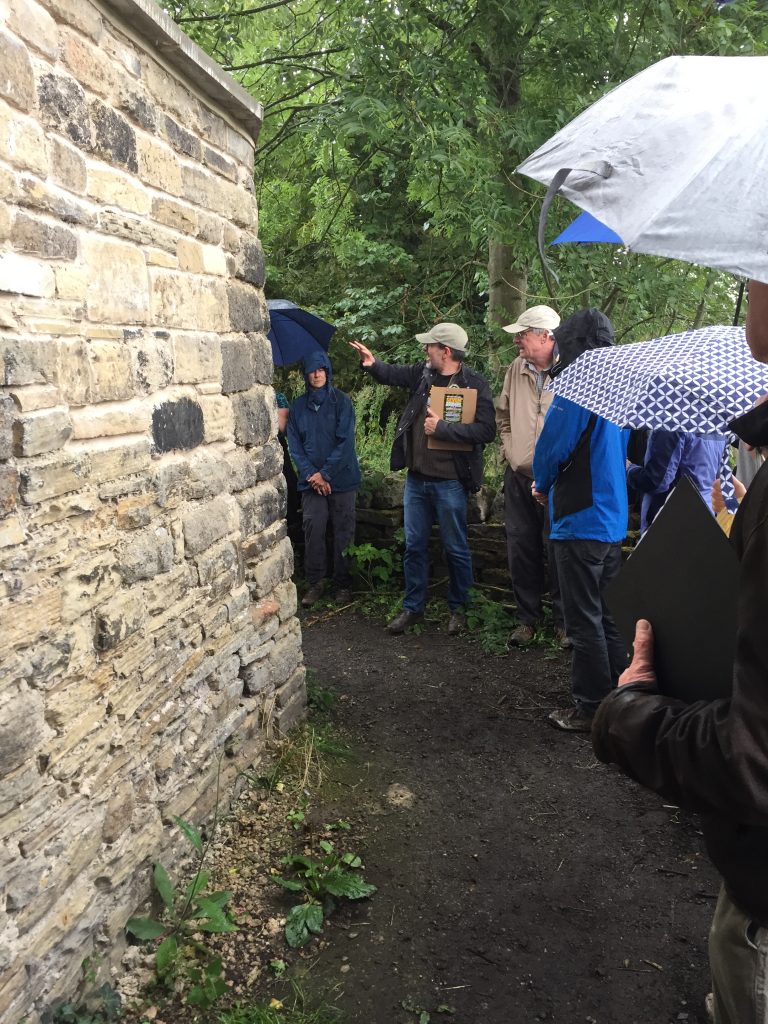

Heading further along Sparable Lane, we turned at corner of the walled gardens on the edge of the Milner Field mansion estate (below). By this stage, the weather had turned towards rain — as you can see from the umbrellas — but we were largely sheltered by trees and it was actually rather nice to get the cooling rain after the walk uphill. The rain then subsided soon enough (unlike the day before…).

Having reached Gilstead, we paused momentarily to consider the blue plaque commemorating Sir Fred Hoyle — famous son of Gilstead, world-leading scientist, and a poet of a different kind… (On radio in 1949, he coined the term “Big Bang” as a put-down to the recently-developed theory, only for it to stick as a descriptor!) Then finally we came to the Milner Field estate…

… here we paused at the entrance gate and gate lodge (‘North Lodge’), which is the best remaining indication of the architectural style of the now ruined mansion. And then it was into the woods to find the ruins themselves… Some of what we found there is recorded on some video clips collected here.

… here we paused at the entrance gate and gate lodge (‘North Lodge’), which is the best remaining indication of the architectural style of the now ruined mansion. And then it was into the woods to find the ruins themselves… Some of what we found there is recorded on some video clips collected here.

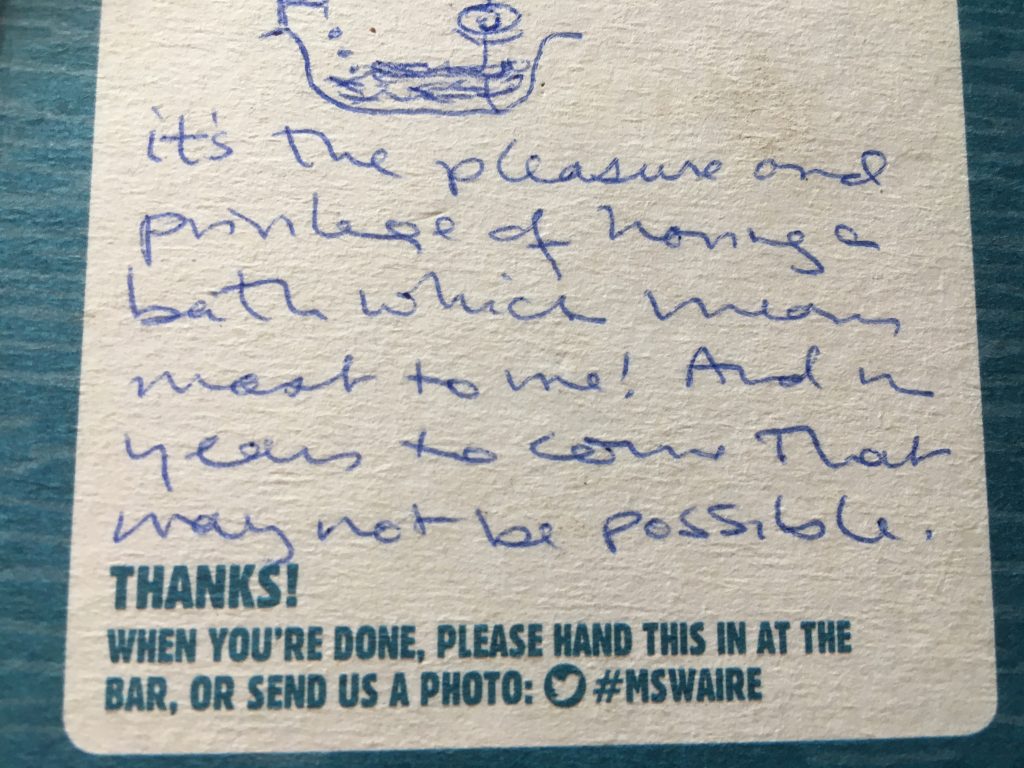

After making our way back downhill through the Milner Field estate, we finished up the walk with a visit to Bradford Amateur Rowing Club’s clubhouse — where we shared a drink and were treated to a number of additional songs from Eddie (who even took requests). The picture above (showing Eddie, me, Molly Kenyon, Rob Martin … others were at the bar at this point!) is courtesy of Denise Boothman, who sent it over to me by email with a note saying “Thanks once again for a fascinating and enjoyable afternoon.” We certainly enjoyed presenting it… Thankyou Saltaire Festival for inviting us to present.

After making our way back downhill through the Milner Field estate, we finished up the walk with a visit to Bradford Amateur Rowing Club’s clubhouse — where we shared a drink and were treated to a number of additional songs from Eddie (who even took requests). The picture above (showing Eddie, me, Molly Kenyon, Rob Martin … others were at the bar at this point!) is courtesy of Denise Boothman, who sent it over to me by email with a note saying “Thanks once again for a fascinating and enjoyable afternoon.” We certainly enjoyed presenting it… Thankyou Saltaire Festival for inviting us to present.

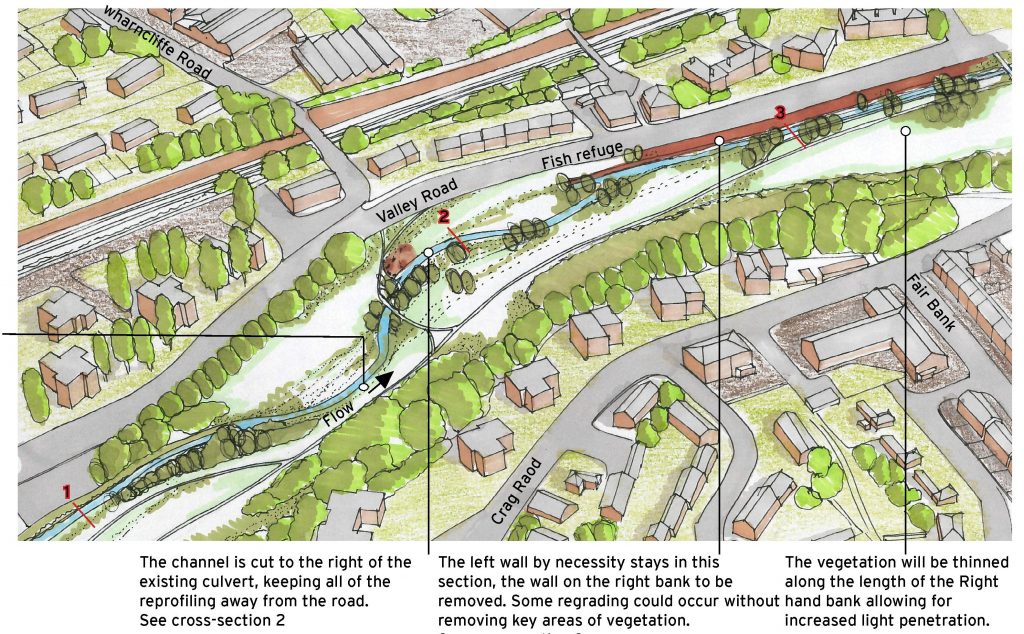

If there’s a slight sense of time-looped deja vu for me here, it’s because I first heard this possibility mentioned back in 2012, at the very beginning of the MSW project, when I was first getting to know Shipley’s rivers. During that same year, Barney Lerner of the

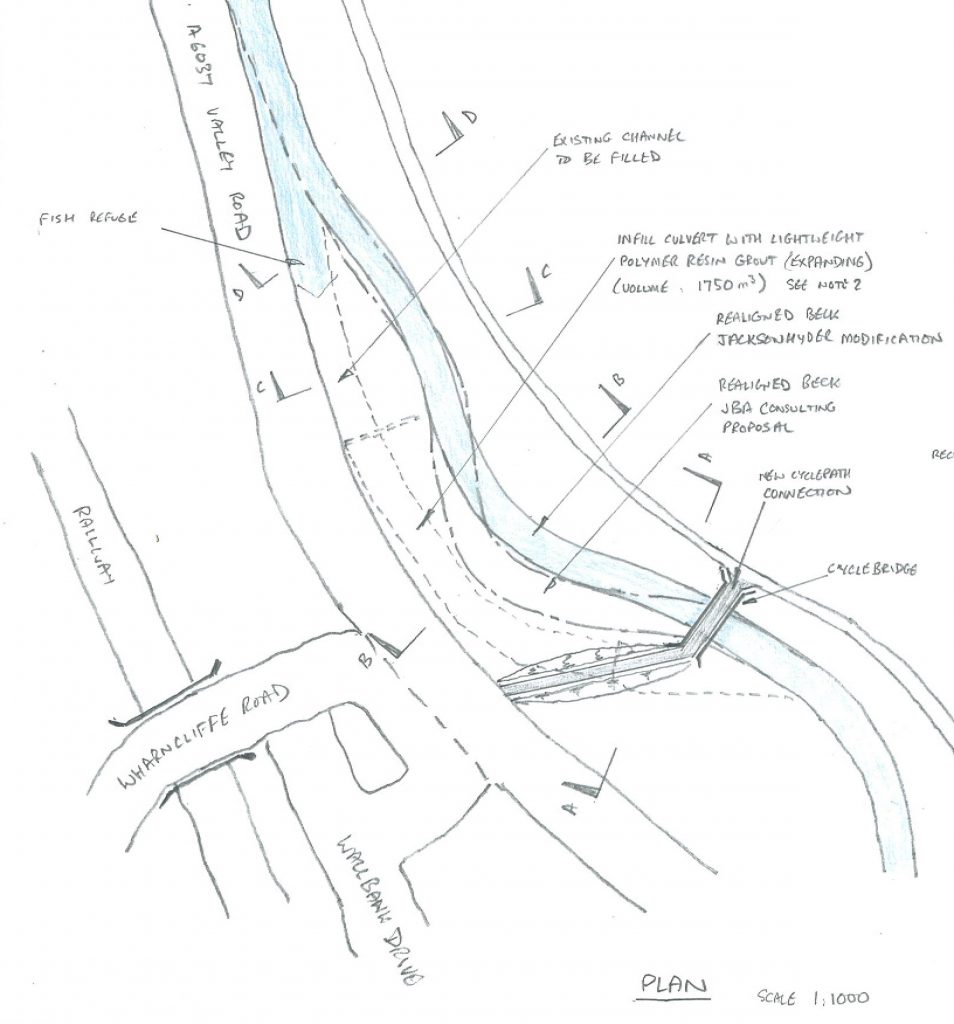

If there’s a slight sense of time-looped deja vu for me here, it’s because I first heard this possibility mentioned back in 2012, at the very beginning of the MSW project, when I was first getting to know Shipley’s rivers. During that same year, Barney Lerner of the  This image, and the drawings below, are reproduced with Barney’s permission from a feasibility study which FoBB commissioned from

This image, and the drawings below, are reproduced with Barney’s permission from a feasibility study which FoBB commissioned from

This is the front cover to a big, map-size document book that I found in the Local Studies section of Bradford Central Library. In 1903/04, Shipley Urban District Council was a pretty new entity, having evolved from the old Shipley Local Board, and it had big plans for Shipley’s regeneration (this involved, for example, a lot of development in the Dockfield area, as

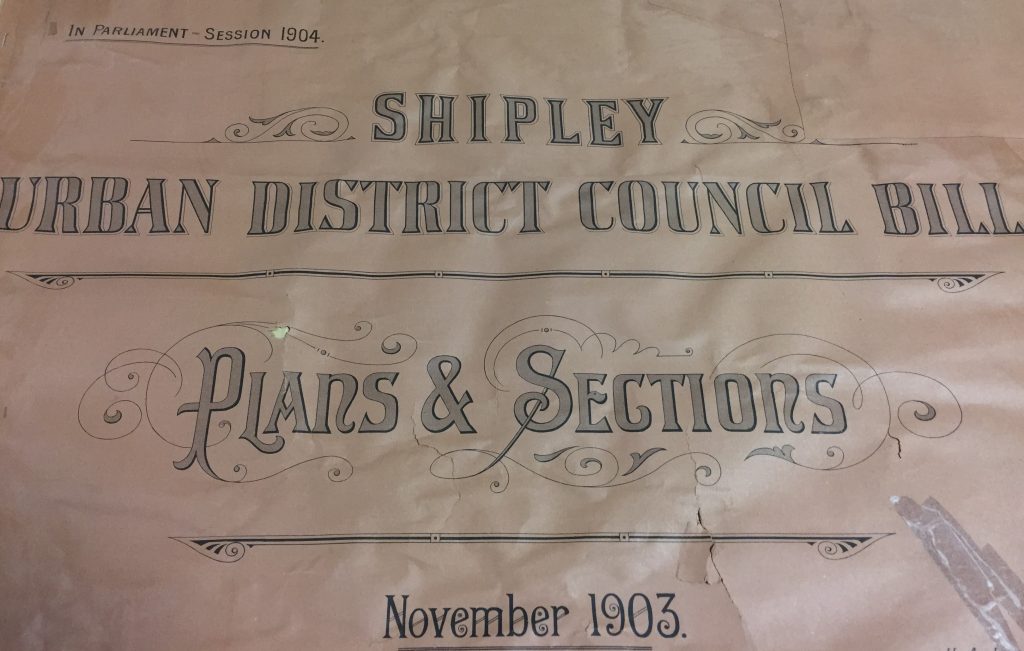

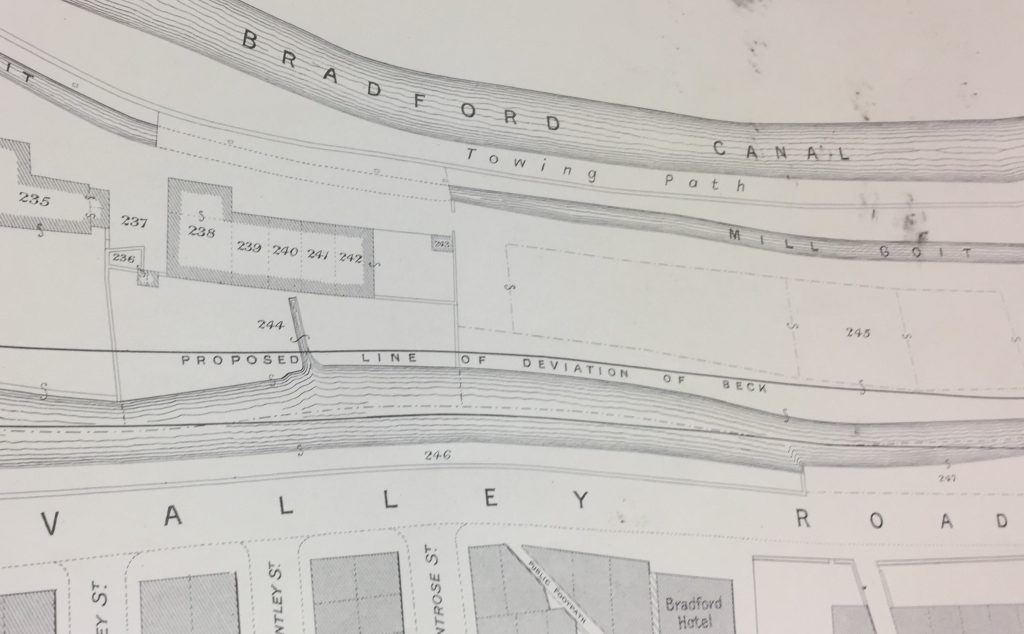

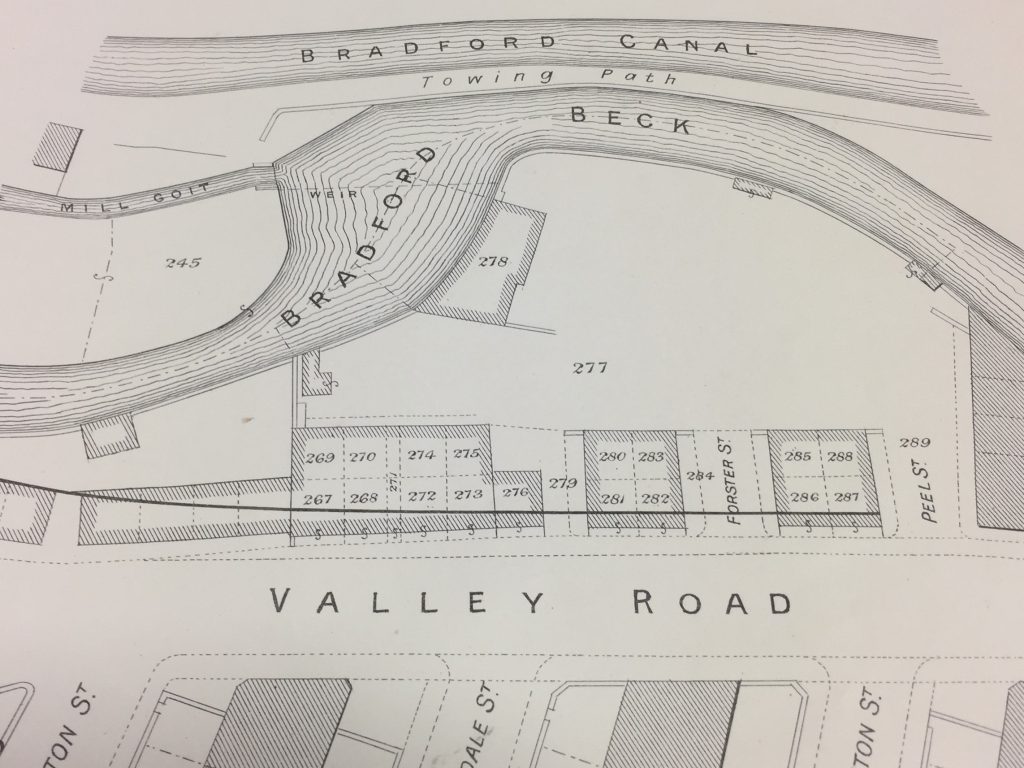

This is the front cover to a big, map-size document book that I found in the Local Studies section of Bradford Central Library. In 1903/04, Shipley Urban District Council was a pretty new entity, having evolved from the old Shipley Local Board, and it had big plans for Shipley’s regeneration (this involved, for example, a lot of development in the Dockfield area, as  In the map diagram above, you can again see Valley Road, and the Beck running alongside it…. together with a plan for re-routing the Beck slightly further east (“Proposed line of deviation of Beck”), further from the road. At the top of the picture runs the then-still-extant Bradford Canal (eventually filled in after its closure in 1922). Now look at the next image, which shows the next segment of Beck/Canal/Road on the way south towards Bradford…

In the map diagram above, you can again see Valley Road, and the Beck running alongside it…. together with a plan for re-routing the Beck slightly further east (“Proposed line of deviation of Beck”), further from the road. At the top of the picture runs the then-still-extant Bradford Canal (eventually filled in after its closure in 1922). Now look at the next image, which shows the next segment of Beck/Canal/Road on the way south towards Bradford…

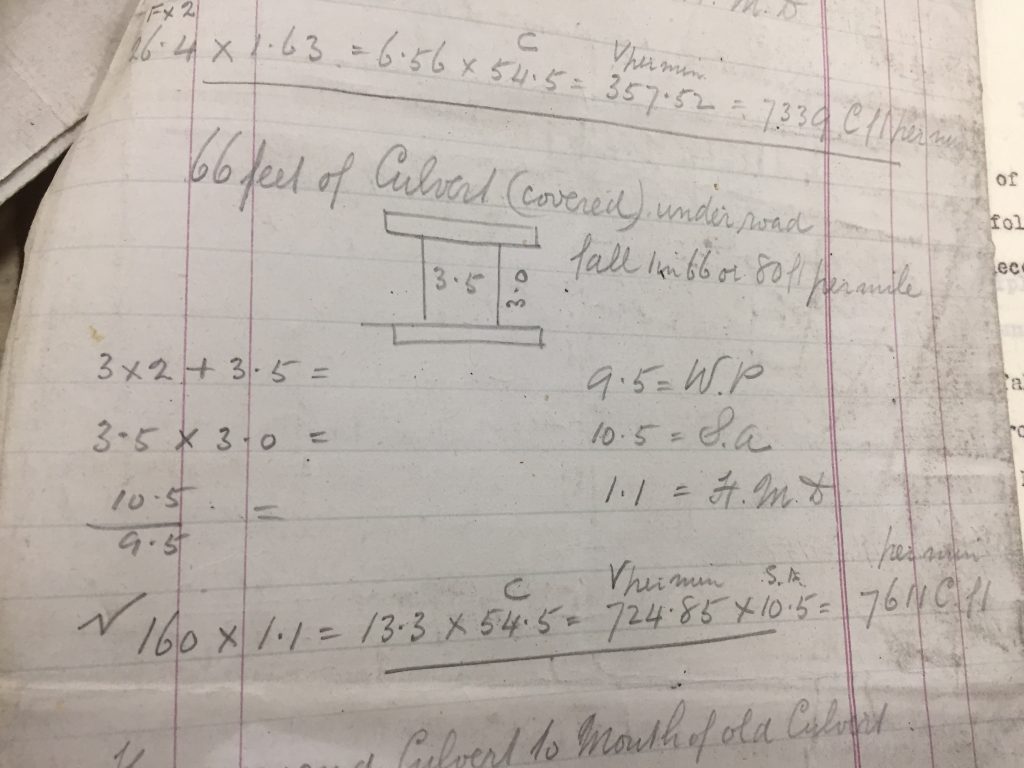

These pencil-sketched engineers’ calculations almost look as if they could have been written yesterday. Don’t ask me what all the numbers mean, but the plan is for “66 feet of Culvert (covered)” — so about 20 metres. I found these sheets of calculations among the Shipley Urban District Council papers held by West Yorkshire Archive Service (to whom, thanks for permission to reproduce this image). The notes are undated, but they’re in amongst other papers relating to SUDC’s early 20th C. redevelopments, and they also provide detailed specifications about other sections of open culverting that this closed culvert will connect to (just as is indeed the case along Valley Road). Is this perhaps a handwritten plan for the construction of the box culvert in question?

These pencil-sketched engineers’ calculations almost look as if they could have been written yesterday. Don’t ask me what all the numbers mean, but the plan is for “66 feet of Culvert (covered)” — so about 20 metres. I found these sheets of calculations among the Shipley Urban District Council papers held by West Yorkshire Archive Service (to whom, thanks for permission to reproduce this image). The notes are undated, but they’re in amongst other papers relating to SUDC’s early 20th C. redevelopments, and they also provide detailed specifications about other sections of open culverting that this closed culvert will connect to (just as is indeed the case along Valley Road). Is this perhaps a handwritten plan for the construction of the box culvert in question?

The location for this research has been Leandra, a township in the Govan Mbeki region (a couple of hours from Pretoria and Johannesburg). As you drive into town, passing this welcome sign, you come immediately to another hoarding warning residents and visitors to save water.

The location for this research has been Leandra, a township in the Govan Mbeki region (a couple of hours from Pretoria and Johannesburg). As you drive into town, passing this welcome sign, you come immediately to another hoarding warning residents and visitors to save water. “What if … this was the last drop?” is a question that, thankfully, I’ve never had to ask myself living in the UK. But it’s a very real issue in Leandra: we arrived on a cloudy day which briefly turned rainy (complete with thunder and lightning), but in 2015-16 they had a significant drought period that impacted severely on the community.

“What if … this was the last drop?” is a question that, thankfully, I’ve never had to ask myself living in the UK. But it’s a very real issue in Leandra: we arrived on a cloudy day which briefly turned rainy (complete with thunder and lightning), but in 2015-16 they had a significant drought period that impacted severely on the community. “Water is life – sanitation is dignity”, reads the small print on the poster. But life and dignity are impacted by more than just water shortage when water is short here. This is a predominantly rural area, whose residents traditionally survived through subsistence farming. Nowadays, what with industrialisation and globalisation, the farms have become big commercial enterprises – with giant maize silos like the ones you see here. In drought conditions, workers on the farms and at the silos simply get laid off because there is not enough work for them to do. And that leaves them unable to buy the food supplies that they would once have grown for themselves…

“Water is life – sanitation is dignity”, reads the small print on the poster. But life and dignity are impacted by more than just water shortage when water is short here. This is a predominantly rural area, whose residents traditionally survived through subsistence farming. Nowadays, what with industrialisation and globalisation, the farms have become big commercial enterprises – with giant maize silos like the ones you see here. In drought conditions, workers on the farms and at the silos simply get laid off because there is not enough work for them to do. And that leaves them unable to buy the food supplies that they would once have grown for themselves…

Let’s get back to that question of water and dignity, though. Because on the face of it, there isn’t much dignity to be had in Leandra. The vast majority of residents live in homes like this… if they’re lucky…

Let’s get back to that question of water and dignity, though. Because on the face of it, there isn’t much dignity to be had in Leandra. The vast majority of residents live in homes like this… if they’re lucky… … or like this, if they’re not so lucky…

… or like this, if they’re not so lucky… In South Africa, they call it “informal housing”. Shacks built of corrugated metal — or anything else lying to hand — get put up without consent or planning permission on land that has simply been appropriated by people too poor to aspire to anything else. Such homes, as you would expect, do not have proper plumbing or sewerage, of the sort we simply take for granted in the UK. Most people have to walk to get water, and the distances they walk get exponentially longer in times of drought. Little wonder, then, that people here are regularly lectured about saving water by the authorities — via billboard messaging of the sort pictured above, as well as by lessons in school, and so forth.

In South Africa, they call it “informal housing”. Shacks built of corrugated metal — or anything else lying to hand — get put up without consent or planning permission on land that has simply been appropriated by people too poor to aspire to anything else. Such homes, as you would expect, do not have proper plumbing or sewerage, of the sort we simply take for granted in the UK. Most people have to walk to get water, and the distances they walk get exponentially longer in times of drought. Little wonder, then, that people here are regularly lectured about saving water by the authorities — via billboard messaging of the sort pictured above, as well as by lessons in school, and so forth.

Almost everywhere you go in Leandra, there is litter like this. I guess when the environment is already poor — in every sense of the word — there’s not much incentive to keep it clean. Apparently such littering is a problem all over South Africa, but nobody really knows what to do about it — and in the great scheme of the problems here, it probably doesn’t rank that high on the priority list.

Almost everywhere you go in Leandra, there is litter like this. I guess when the environment is already poor — in every sense of the word — there’s not much incentive to keep it clean. Apparently such littering is a problem all over South Africa, but nobody really knows what to do about it — and in the great scheme of the problems here, it probably doesn’t rank that high on the priority list.

In this picture, these performers look like what they are — kids! — but in performance they were nothing short of awe-inspiring. On the small stage of the community centre, they presented a sequence of drumming, dancing and choral singing — and every possible combination of the three — which ran for over 15 minutes without a pause. Every time a particular sequence finished (a pounding high-kick routine replaced by a quiet, reflective song, for example) they moved from one phase into the other with such tightness and precision that there wasn’t even time for applause. And the sound of the pounding drums and thumping feet was almost overwhelming in that small hall. I was, as you can probably tell, blown away by the whole thing!

In this picture, these performers look like what they are — kids! — but in performance they were nothing short of awe-inspiring. On the small stage of the community centre, they presented a sequence of drumming, dancing and choral singing — and every possible combination of the three — which ran for over 15 minutes without a pause. Every time a particular sequence finished (a pounding high-kick routine replaced by a quiet, reflective song, for example) they moved from one phase into the other with such tightness and precision that there wasn’t even time for applause. And the sound of the pounding drums and thumping feet was almost overwhelming in that small hall. I was, as you can probably tell, blown away by the whole thing! The “Patterns of Resilience” project — run by the remarkable Angie Hart, from the University of Brighton, in collaboration with colleagues at the University of Pretoria and elsewhere — has focused specifically on engaging 43 young people from Leandra as “co-researchers” in learning about resilience to drought. They were even paid something to take part (an ethical way for the research team to put some of their funding into the community itself, while also valuing the young people as co-workers, not just volunteers). The research has included arts-based activities that have helped the young people to process and reflect on their own thoughts, feelings and coping strategies during the recent drought of 2015-16. It has also involved training them up as interviewers, to go and talk to elders within the community, such as grandparents, about their memories of drought over the longer term. Through this process, the young people have learned valuable things about themselves and their community, as well as providing the university researchers with important insights (some of which I’ve already mentioned in this blog).

The “Patterns of Resilience” project — run by the remarkable Angie Hart, from the University of Brighton, in collaboration with colleagues at the University of Pretoria and elsewhere — has focused specifically on engaging 43 young people from Leandra as “co-researchers” in learning about resilience to drought. They were even paid something to take part (an ethical way for the research team to put some of their funding into the community itself, while also valuing the young people as co-workers, not just volunteers). The research has included arts-based activities that have helped the young people to process and reflect on their own thoughts, feelings and coping strategies during the recent drought of 2015-16. It has also involved training them up as interviewers, to go and talk to elders within the community, such as grandparents, about their memories of drought over the longer term. Through this process, the young people have learned valuable things about themselves and their community, as well as providing the university researchers with important insights (some of which I’ve already mentioned in this blog).