The title Salt’s Waters refers to a number of different versions of a words-and-music collaboration between Multi-Story Water researcher Steve Bottoms and the ‘Bard of Saltaire’, Eddie Lawler. These versions are as follows:

First and foremost, Salt’s Waters (2016) is a downloadable audio tour for smartphone or mp3 player, which guides walkers in a circular adventure from Salt’s Mill, Saltaire, up the ruins of Milner Field House at Gilstead, via the River Aire, Loadpit Beck, and Little Beck, before returning via the Aire and the Leeds-Liverpool Canal. In addition to Steve’s narration, and other voices performed by Rob Pickavance, the audio tour features Eddie Lawler’s song ‘The Ballad of Little Beck’, which was written especially for the context, and tells the story of Milner Field in words and music. For full information and download instructions, click here.

First and foremost, Salt’s Waters (2016) is a downloadable audio tour for smartphone or mp3 player, which guides walkers in a circular adventure from Salt’s Mill, Saltaire, up the ruins of Milner Field House at Gilstead, via the River Aire, Loadpit Beck, and Little Beck, before returning via the Aire and the Leeds-Liverpool Canal. In addition to Steve’s narration, and other voices performed by Rob Pickavance, the audio tour features Eddie Lawler’s song ‘The Ballad of Little Beck’, which was written especially for the context, and tells the story of Milner Field in words and music. For full information and download instructions, click here.

A work-in-progress version of the audio walk, tracing the same route, was conducted under the same title as a guided group walk on April 19th, 2015, as part of Saltaire’s World Heritage Weekend (blog account here).

Finally, a live, cabaret-style version for seated audiences was also developed alongside these mobile versions of Salt’s Waters, and performed in a number of contexts. This too was originally treated as ‘work-in-progress’ development for the audio guide, but the concert version gradually acquired a life of its own, not least because it enabled a more extensive use of Eddie’s expanding catalogue of water-related songs. Over successive versions of the piece, the selection of songs and the narrative line of Steve’s accompanying narrative became clearer and tighter. An accompanying slide-show was also developed to provide visual context.  Live versions of Salt’s Waters were presented on the following occasions:

Live versions of Salt’s Waters were presented on the following occasions:

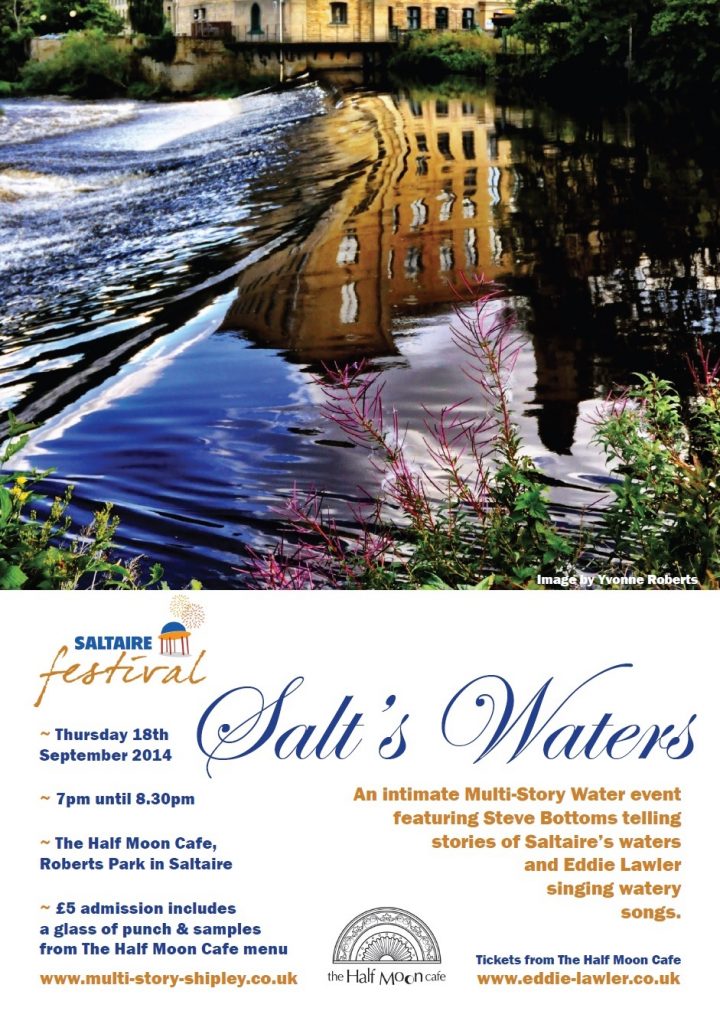

18th September 2014 @ Half Moon Cafe, Roberts Park, for Saltaire Festival

15th September 2015 @ Half Moon Cafe, again for Saltaire Festival

6th October 2015 @ Comrie Croft, Perthshire, for Waterlution‘s Water Innovation Lab (supported by the Scottish Government)

7th December 2016 @ John Thaw Studio Theatre, University of Manchester

22nd July 2017 @ Kirkgate Centre, Shipley, for Multi-Story Water’s exhibition launch

The presentation was adjusted for context slightly each time we performed it. For the record, however, a representative version of the performance text is reproduced below with accompanying images.

All song lyrics are ©Eddie Lawler www.eddie-lawler.co uk. Reproduced with permission.

SALT’S WATERS (sit-down version)

We begin with Steve and Eddie launching into the chorus of Eddie’s song ‘Welcome to Our Airedale Home’. They sing it through once, then encourage the audience to join them in a reprise:

Welcome to our Airedale Home / We’re glad to see you all here

We’ll go and put the kettle on / If you’ll just sit yersen in a chair

There’s allus a welcome around if / You leave the place as you found it

Cos we’ll not have no messin’ around with / Our ‘andsome Airedale ‘ome!

STEVE. Airedale. A long, eastward valley carved out by the movement of a glacier, eleven and a half thousand years ago. A valley down which flows the River Aire… moving from limestone moors to millstone grit. And along the way, coming down from all those Yorkshire hills, at frequent intervals, there are streams and becks and rivulets that swell the main river as it goes, like liquid soldiers joining an expanding army as its marches toward the sea.

But it’s all just water, right? That stuff that comes out of a tap? These days we often just think of water as a singular substance – a quantifiable resource to be captured and treated, piped and channelled, bought and sold. But prior to the nineteenth century — prior to the modern scientific era of H20 — prior to the modern industrial era of resource exploitation — people tended to be more interested in how waters were different, than in the ways they were the same. Waters tasted very different, for instance, depending on the mineral landscapes they moved through. And waters represented aspects of the histories of places — their stories told in folklore, religion and natural philosophy..

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Salt’s Waters. A site-specific celebration of waters in the Airedale vicinity of Bradford. Allow me to introduce my good friend Eddie Lawler, on guitar and lead vocals. Eddie may also improvise his own commentaries from time to time. But I’m Steve Bottoms and I will be sticking rigidly to this script.…

Eddie sings the following song, a capella. It’s in the voice of Emily Bronte, although there’s a lot of Eddie in here too…

EMILY’S SONG

I love the hills of Yorkshire / I am a part of the Pennine moors

The valleys with all variations of green / The sun, the clouds mirrored in the stony walls

I feel so at home here somehow / It’s as if I’d been shaped with the land

There’s mystery and wild magic around / Yet seems made by a familiar hand

It’s a home of hard and soft the same time / It’s both grim and gentle in its guise

Gives the feeling true that my feet are free / And some other part deep down inside

It’s to do with something I will call REAL / Moments of heaven, moments of hell

Through pleasure & passion, through torment & pain /Till the beauty rings out like a bell

It’s to do as well with my Irish father / Whose Cornish lady lies long in the grave

The colour of his hair upon my head / His inscrutability in my face

Perhaps Mourne Mountains gave him the gift / For there’s poetry runs through his prose

A fire that of a sudden ignites in the breast / He has a music that strikes the soul

(repeat first verse, to end)

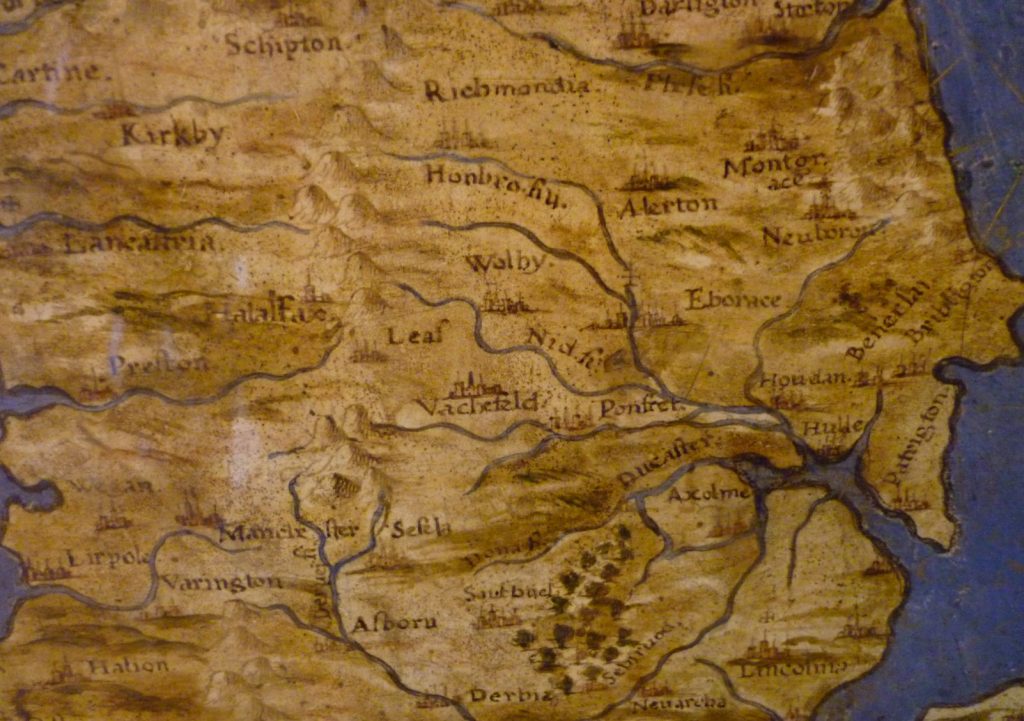

STEVE: Tuscany is a long way from Yorkshire. But in the glorious city of Florence, there lies the Palazzo Vecchio – a building that boasts Michaelangelo’s David as its doorman. Inside the Palazzo, there is an upstairs room that was once the office of Niccolo Machiavelli. Directly next door to that lies the map room of the Medicis. In the fifteenth century, the Medicis were the most powerful family in the world, and that power derived in part from their unmatched intelligence networks. The map room is a treasure trove of parchments, illuminated in gold leaf, laying out everything that was then known about the shape of the world… and in one corner, the distant British Isles are still on display.

What is most remarkable is just how accurate the map appears … Wales is a bit squashed, Ireland is distinctly wonky, but the outlines of every part of these islands – right up to the Scottish Hebrides – are nevertheless unmistakable. That’s presumably because the Italian spies did most of their mapping by water. By boat.

What is most remarkable is just how accurate the map appears … Wales is a bit squashed, Ireland is distinctly wonky, but the outlines of every part of these islands – right up to the Scottish Hebrides – are nevertheless unmistakable. That’s presumably because the Italian spies did most of their mapping by water. By boat.

For the same reason, the mapping of Yorkshire is characterised mostly by its numerous, snaking rivers. There is Richmondia, near the head of what must be the River Swale. There is Vachefeld – Wakefield – accurately mapped to the River Calder. “Halaifax” seems to have drifted across towards Lancashire, somewhere in the proximity of Preston, because the Italians apparently decided against trying to make proper sense of the high Pennines. But there, on the River Aire, is a town called “Leaf.” Leeds.

For the same reason, the mapping of Yorkshire is characterised mostly by its numerous, snaking rivers. There is Richmondia, near the head of what must be the River Swale. There is Vachefeld – Wakefield – accurately mapped to the River Calder. “Halaifax” seems to have drifted across towards Lancashire, somewhere in the proximity of Preston, because the Italians apparently decided against trying to make proper sense of the high Pennines. But there, on the River Aire, is a town called “Leaf.” Leeds.

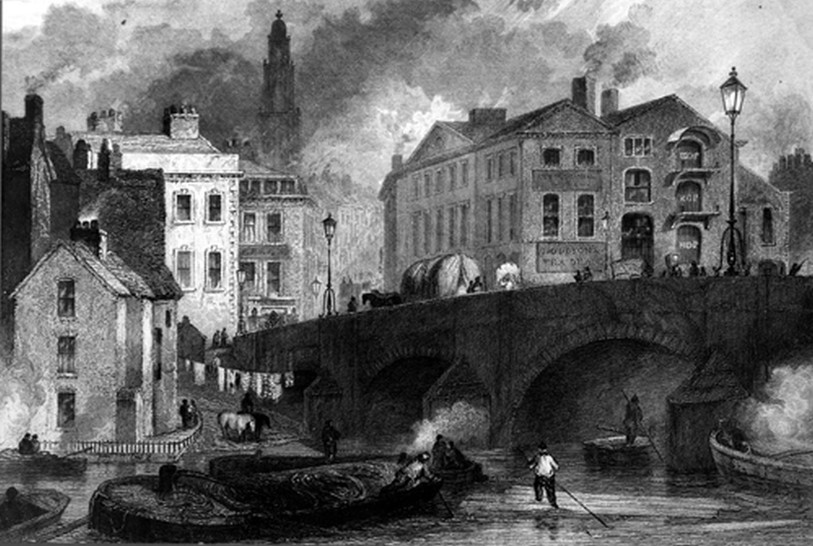

In the fifteenth century, when Bradford barely existed as a concept, Leeds – twelve miles downstream along the Aire — was already the centre of Yorkshire’s woollen trade. Leeds Bridge, a mighty stone bridge that had spanned the Aire at the bottom of Briggate since the mid-14th Century, was the site of the Leeds Cloth Market. For a matter of centuries, every Tuesday and Saturday, cloth merchants would come from south and north of the river to display their wares on the bridge’s stone parapets…

But what really cemented Leeds’s lead in the Yorkshire wool race was the Aire and Calder Navigation. A grand scheme to canalise parts of the River Aire – and the neighbouring Calder – so that quite sizeable freight boats could make their way 70 miles inland from the sea.

But what really cemented Leeds’s lead in the Yorkshire wool race was the Aire and Calder Navigation. A grand scheme to canalise parts of the River Aire – and the neighbouring Calder – so that quite sizeable freight boats could make their way 70 miles inland from the sea.

(Eddie introduces an early 18th ‘broadsheet ballad’ satirising the opening of the Aire and Calder Navigation… The audience is encouraged to join in with the Chorus.)

When Leeds becomes a Seaport Town

Oh dear, oh dear! This is curious age is / Alteration all the rage is

Young and old in the stream are moving / All in the general cry improving

From the Yorkshire Post I’ve brought news down /They’re going to make this a seaport town

Instead of factories and cheap tailors /Nothing you’ll see but ships and sailors

Chorus: (x2) Thus ’twill be, I’ll bet you a crown / When Leeds becomes a seaport town

When the first ship comes into sight / The town will be full of joy and delight

Eating, drinking, dancing, singing / The old church spire will shake with ringing

Then shall we meet with the touts and prigs / The Aldermen in their gowns and wigs

The toffs of the town in all their forces / And the Lord Mayor driven by coach and horses

(Repeat Chorus)

The town will be full of boats and barges / Man o’ war ships of the very largest

Steamers backward and forward towing / You’ll ride for nothing, they’ll pay you for going

Sailors swearing, spars a-battering / Heave-hoing with capstans clattering

Ships from near and very far away / Sailing and anchoring in Leeds bay

(Repeat Chorus)

[this next verse is Eddie’s own update on the original ballad]

The Custom House is the Corn Exchange / On Harvey Nick’s there’ll be harbour cranes

All the city-centre cafes and boozers /Packed with folk from round-the-world cruises

City Square draped in fishermen’s nets / Lobster-pots on the Town Hall steps

Listen to the singing of the gondoliers / Or take a long walk on the half-mile pier

(Final Chorus)

STEVE: Leeds became a seaport town at the beginning of the 18th century, and the ripples of that change quickly began to be felt in the surrounding landscape. Cloth manufacture remained primarily a small scale, domestic affair. But that didn’t mean that there weren’t would-be tycoons seeking to “scale up” even before the technology would really permit it…

Sir Walter Calverley was, by right of birth, Lord of the Airedale Manors of Calverley, Yeadon and Esholt. He was the direct descendant of another Sir Walter Calverley, whose brutal murder of his own wife and children had made him the subject of a 1608 play – A Yorkshire Tragedy — credited on its frontispiece to one William Shakespeare (although scholars now doubt the attribution).

Sir Walter Calverley was, by right of birth, Lord of the Airedale Manors of Calverley, Yeadon and Esholt. He was the direct descendant of another Sir Walter Calverley, whose brutal murder of his own wife and children had made him the subject of a 1608 play – A Yorkshire Tragedy — credited on its frontispiece to one William Shakespeare (although scholars now doubt the attribution).

Our Sir Walter was no murderer, but he knew a few ways to make a killing. In the years following the opening of the Aire-Calder Navigation, he looked upstream towards Shipley to begin an expansionist land grab. (He must have smelled profit in the Aire.) In 1711, Sir Walter bought up the century-old Dixons Mill — “farmland, two barns, three cottages, one water corn mill, two fulling mills, and the several fields and closes lying near to in Shipley and Baildon.” In 1712, he bought another property slightly further upstream – “those two fulling mills commonly called Hirst Mill, together with one dwelling house and barn adjoining, and all the dams, floodgates, goyts etc.” Two years later, 1714, Sir Walter added yet another water mill to his collection – Buck Mill – by purchasing the Lordship of the Manor of Idle, just downstream of Shipley. Already the owner of two other mills by virtue of his inherited lands, he now had a portfolio of five Airedale water mills. Historians believe that his motivation was to “encourage his tenants in the domestic woollen trade.”

One of those tenants was Samuel Denison, to whom Sir Walter leased both Dixons Mill and Hirst Mill in 1716 – for a period of 21 years at a rent of £120 per annum. A little bit of maths tells us that, by the end of that period, Sir Walter would have made back the purchase price of these properties twice over, while still owning them. Samuel Denison, the tenant, must have looked at Sir Walter, his landord, lining his pockets with the fruits of Samuel’s sweat, and wondered what he was doing wrong. By 1745, he decided to buy his own land. Purchasing a riverside tract yet further upstream — at the far side of Hirst Wood — Denison set about building Hirst New Mill, a new fulling mill with no less than eight stocks. Samuel Denison, however, was not a hereditary landowner. Having spent three decades giving away much of what he had earned as a miller in ground rent, he paid for the new mill by over-extending himself with mortgages. After only two years on site, in 1747, Denison was forced to forfeit land and mill to his creditors. A note in the Shipley town records dated 1750 describes him simply as “bankrupt. Deceased.”

The new, aspirant middle class of Yorkshire had to wait another quarter century before the means to really turn a profit came onstream. In 1774, a new canal opened — running in close parallel with the River along the Aire valley – and thus passing close by all three of the Shipley water mills that Samuel Denison had once operated. The canal opened up a waterborne freight route to and from Leeds, and when eventually completed it extended all the way up and over the Pennines, then downhill again, via Wigan, to Liverpool, on the west coast.

(Eddie sings his next composition alone, without choral support.)

CANAL CHILD

I’m a Canal Child, born on a boat / Brought up to help keep a family afloat

My home’s a cabin just 14 foot wide / But as long as wherever we travel outside

That’s one hundred and twenty-six mile

I may not be learning to read and to write / But I’m learning to paint for to keep the boat bright

I can open the locks and can harness the horse / Can look at a load and say just what it’s worth

Soon as I’m able I’m one of the crew / Morning till bedtime there’s so much to do

Some people tell me I should be at school / Well my school is as long as the Leeds-Liverpool

That’s one hundred and twenty-six mile

And I don’t go down mines to get buried in muck / Not climbing up chimneys to sweep out the soot

Nor scrabbling round under thundering looms / I get my fair share of fresh air in my lungs

In winter we might be marooned in the ice / But the dawn chorus tells us when spring has arrived

We’ve a parrot called Polly and the horse is called Joe / Polly shouts “Gee-up” and then she shouts “Whoah!”

For one hundred and twenty-six mile

For a canal child, life can be tough / The folk on the bank may look down upon us

But we’re earning our crust and we’re learning the ropes / Living on water and living in hope

For one hundred and twenty-six mile

(Repeat first two lines of first verse)

STEVE: With the Aire and Calder Navigation already providing a waterway to the North Sea, the opening of the Leeds-to-Liverpool Canal opened up a coast to coast water corridor. What its name disguises, though, is that this hugely ambitious project was actually initiated in Bradford. In the 1770s, Bradford was a modest market town of only 6,000 souls, but the local businessmen were dreaming big… A grand canal running through Airedale would pass within 4 miles of their previously secluded town. All that was needed was a small branch cut – the Bradford Canal – which could connect with the main canal at Shipley. The Bradford Canal was, in fact, cut at the same time as the very earliest sections of the Leeds-to-Liverpool. So as more and more sections of the canal were completed, Bradford’s textile manufacturers could reach an ever-wider market…

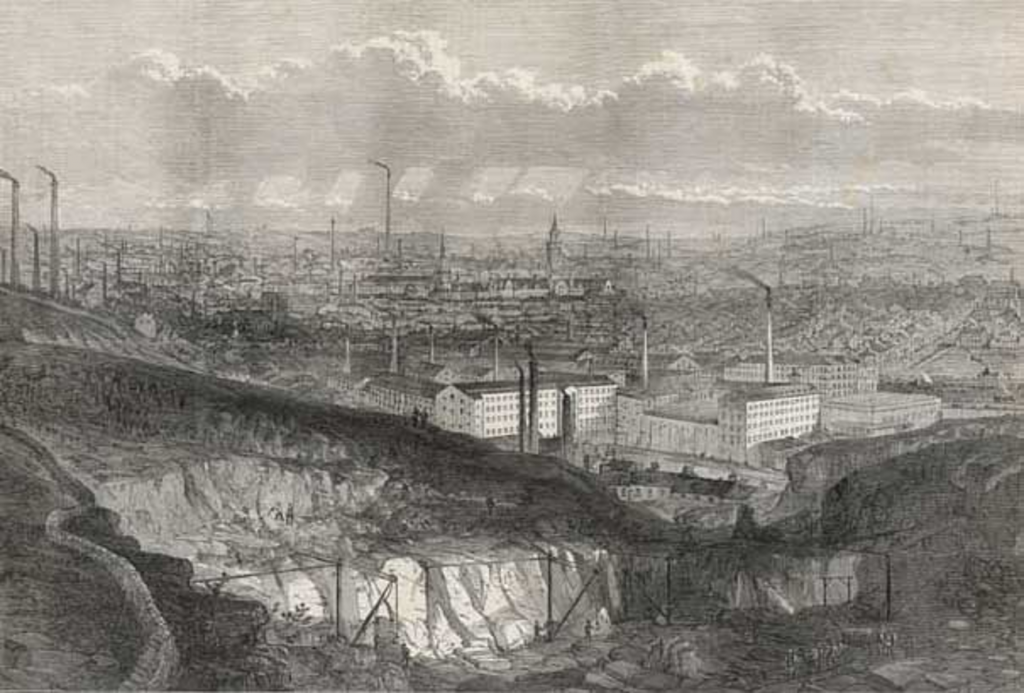

Cut to the mid-19th Century. The height of the industrial revolution. Thanks to its thriving woollen industry, Bradford is the fastest growing city in Victorian England – possibly the world. Yet this new capital of capitalism faced a permanent headache in the shape of its vital transport link. To take a cargo boat along the three and a half miles of the Bradford Canal, from the Shipley junction up to Hoppy Bridge, you had to go through no less than ten locks – including three two-rises, and a three-rise at Crag End. This meant that, at busy times, with boats having to wait for each other to come and go at these long, thin bottlenecks, it could take up to three days to get a cargo into the centre of town.

Worse still was the issue of water quality. To feed the lock system, which constantly sent water escaping downhill towards Shipley, the canal company drew water from Bradford’s small river, the Bradford Beck – which flowed along the same valley to its intersection with the River Aire, at Shipley.

Once a trout stream as clear and bright as any in Yorkshire, the Beck was now treated by Bradford’s residents and factory owners alike as an open sewer. This was water that ran literally black with industrial effluent – chemicals and heavy metals. This water, once siphoned off into the canal, where it had no current, just sat there … stinking. It was, in the words of the Bradford Observer, a “seething cauldron of all impurity.”

(Eddie launches straight into the next song. The audience learns the Chorus as we go…)

BRADFORD CANAL

Attention all passengers aboard this boat / Here’s a health warning before we start

Draw a deep breath if you intend to sing / ’Cos this … song … STINKS!

Now the life of a bargeman’s not cosy or easy

But he doesn’t get scurvy and he shouldn’t get seasick

With a boat for a his home and a family for crew

There’s goods to be carried and plenty to do

But there’s one trip too far for a bargeman’s morale

That’s taking a cargo on the Bradford Canal

Chorus:

Oh the stink, oh the smell / You’ll be forgiven for thinking it’s hell

Oh the stink, oh the smell / Steer well away from the Bradford Canal

It’s a navvy-built section from t’ Liverpool-Leeds

Making Bradford’s connection to West and to East

From Shipley Junction it’s just three-and-half miles

But with ten locks to tackle takes more than a while

And once you’ve unloaded at t’ Hoppy Bridge end

It’s ten locks all over to get out again

(Repeat Chorus)

As transport for boats what’s the water was meant

But this stretch of water’s a deadly dead-end

Not used just for transport but everything else

Especially the nasty stuff poured out from t’mills

Which spring up like mushrooms along both its banks

Manufacturing water that’s reeking and rank

(Repeat Chorus)

To t’solvent and dyestuff from t’making of cloth

Add human detritus tipped neat into t’broth

Which wafts all round Windhill when t’ wind blows from t’West

And spreads typhus and cholera to those who ingest

The contents explosive, it might well ignite

By t’ Bradford Canal, please … no naked lights!

Chorus: Oh the stink, oh the smell

Steer well away from the Bradford Canal

Oh the stench, oh the reek

The odour will stick with you many a week

Oh the niff, oh the pong

You’ve just been singing the smelliest song

Oh the stink oh the smell

Steer well away from the Bradford Canal

STEVE: In 1849, 406 people died in a cholera epidemic in the canal’s vicinity, prompting an elongated legal argument about the appalling sanitation conditions. In 1867, the Bradford Canal was finally shut down until a safer water supply could be engineered. It remained closed for five years, much to the distress of local factory owners, who still depended on it as a vital freight route.

Not, however, Sir Titus Salt. One of the city’s leading industrialists, Sir Titus had seen the writing on the wall. In 1850, the year after the cholera epidemic, he had begun buying up land in the Shipley area. Why trust your commercial future to an inefficient branch line, that might get closed down as a public health risk, if you can to relocate yourself onto the mainline? In 1853, Sir Titus opened Salts Mill – then the largest mill building in the world – on the banks of the Leeds-Liverpool Canal. He also began building a model village of workers’ houses, with proper sanitation and drainage. Then, in 1867, he opened another mill – New Mill – on the riverside site once occupied by Dixon’s water mill. But Sir Titus didn’t need waterwheels. His was the age of steam.

Not, however, Sir Titus Salt. One of the city’s leading industrialists, Sir Titus had seen the writing on the wall. In 1850, the year after the cholera epidemic, he had begun buying up land in the Shipley area. Why trust your commercial future to an inefficient branch line, that might get closed down as a public health risk, if you can to relocate yourself onto the mainline? In 1853, Sir Titus opened Salts Mill – then the largest mill building in the world – on the banks of the Leeds-Liverpool Canal. He also began building a model village of workers’ houses, with proper sanitation and drainage. Then, in 1867, he opened another mill – New Mill – on the riverside site once occupied by Dixon’s water mill. But Sir Titus didn’t need waterwheels. His was the age of steam.

The following decade, Salt’s empire extended a little further west with the purchase of Hirst Mill. It’s almost as if Sir Titus was following in Sir Walter Calverley’s footsteps. He died, though, before he could put into effect whatever grand scheme he had for this site…

Just across the River Aire from Hirst Mill, on the downstream side of the weir, a small stream empties out into the main river. Loadpit Beck, which once ran reddy brown with the mineral deposits that gave it its name, marks the traditional boundary line between the parishes of Baildon and Bingley. If we track the Beck uphill a little, and then turn left along a chestnut-lined avenue, we come to the gatehouse lodge for Milner Field, the great country house built here in the 1870s by Titus Salt Junior.

Just across the River Aire from Hirst Mill, on the downstream side of the weir, a small stream empties out into the main river. Loadpit Beck, which once ran reddy brown with the mineral deposits that gave it its name, marks the traditional boundary line between the parishes of Baildon and Bingley. If we track the Beck uphill a little, and then turn left along a chestnut-lined avenue, we come to the gatehouse lodge for Milner Field, the great country house built here in the 1870s by Titus Salt Junior.

The great driveway has become so overgrown that no carriage could pass here now. But if we track our way through the undergrowth, we eventually come to another small stream, trickling downhill to meet the Aire, from its source not far away in Eldwick. This is Little Beck, once dammed by Titus Salt Junior, to create a scenic boating lake…

(Eddie begins to pick out the chords for ‘The Ballad of Little Beck‘)

The following, contemporary account, describes Milner Field as it once was…

“Not one twig broke the neatly rounded contour of the hawthorn hedge on either side of the mile long drive. Not one weed marred the vast expanse of gravel in the great courtyard in front of the house. . . [Inside,] there was a Louis Quinze drawing room, all gold and green with a grand piano to match. There was a Hepplewhite dining-room, with scarlet leather seats to the chairs. There was a vast library… all velvet with bobbly tassels … Mullioned, casemented windows looked out on smooth expanses of velvety lawns, grey balustrading, and cypress-dark topiary. . . The dogs were all gun dogs. The lake was stocked with trout.”

THE BALLAD OF LITTLE BECK

I know exactly where I’m from / And I know where I will go

I’m born of raindrops poured from cloud / And I run to the river below

I know / I run run run run to the river below

I’m a modest English stream / I’m scarcely two miles long

And yet the sights that I have seen / Are more than enough for a very sad song

For the best-laid plans of wealthy men / To climb to the top of the tree

Have crumbled to nothing before my eyes / In less than a century

(Come and see) / In less than a century

STEVE: All that remains of Milner Field house now is rubble. Here – a pile of random masonry. There – a curiously flat expanse of ground – ground that was once a croquet lawn, but where hoops and players alike have long since morphed into tall young trees, as the forest reclaims its own. And what’s this? A trickle of running water, emerging from under the croquet lawn, shielded by brick housing… perhaps all that remains of the spring that once provided the house with its own, private water supply…

So I sing my song as I tumble on my way / And mainly to myself

So I sing my song as I tumble on my way / And mainly to myself

But I don’t mind anyone listening / If you’re seeking a tale to tell

But listen well / If you want a good tale to tell

My home is all green, briar, bramble / Bracken, nettle, but first in spring

There’s a yellow celandine carpet / Then bluebells as if the sky had fallen in

Wild boar have drunk from my water / Shy deer skipped over my banks

Red squirrels have seen their reflection / From an overhanging branch (as they ran)

On a bending, bouncing branch

But suddenly I am enlisted / Diverted, channelled, dammed

Right next to a mill-owner’s mansion / I’m part of his grandiose plan (yes I am)

I’m part of a mganificent plan

For he’s built his country residence / Away from the smoke and the din

And I fill a lake for little rowing-boats / With fine trout and white water-lilies in

By the crocquet-lawn the huge hothouse / Holds melons, orchids and palms

And flowers from the corners of the wide world

With long long long Latin names (to amaze) / With long long unpronouncable names

The hothouse conservatory at Milner Field is just about the only part of the house still clearly identifiable to the casual visitor. An expanse of concrete flooring, ringed by a low kerb that once edged the flower beds. In the middle of the floor, the fading remains of a mosaic tile design.

So an Englishman built his castle / At enormous expense, to impress

And it did, it caused a sensation / When royalty rolled in as guests (yes your Highness)

A Prince and Princess as guests

But the young owner fell to a heart-attack / And all who took on the estate

Were visited by misfortune / One after another met a terrible fate

Titus Salt Junior. Age 44. Good general health. Dies of sudden heart failure in the Billiard Room at Milner Field.

James Roberts, the next Managing Director of Salts Mill. Watches all four of his sons die young, three of them while living at Milner Field.

Ernest Gates, the next Managing Director of Salts, loses his wife Eva to “an obscure disease” within weeks of moving in at Milner Field. Eighteen months later, age 51, Gates himself dies of septicaemia.

Arthur Hollins, the next Managing Director, loses his wife Anne to pneumonia, the year after moving in at Milner Field. Three years later, age 51, Hollins himself dies of a respiratory condition that had reduced him to unstoppable hiccupping…

- Hollins’s sons abandon the house their parents died in. It has been occupied for less than sixty years.

So the house gained a reputation / And sought for a buyer in vain

Then the thieves and the vandals did their best

Till the wrecking-ball and bulldozer came (shame shame)

Till the growling bulldozer came

A gnarled old beech tree still stands there / It has seen the great house born and die

And some time soon it will end its life / But I will continue with mine (a long time)

Yes I will continue with mine

The stones that are left are now shrouded in green / With lichen and moss for a cover

And everywhere ivy is winding its wreath / But I am no gloomy old funeral-lover

For I’m back to chuckling my own little way / Returned to familiar habits

And what was a lake is a tangle of trees / And the dam’s been busted – by rabbits

Though the squirrels have faded from red to grey / And the wild boar’s only a symbol

The shy skipping deer are once again here / And life is mysterious – yet simple

The great houses of the Salt dynasty. Milner Field to the west, Ferniehurst to the east, the Knoll, even Titus Senior’s home the Crow Nest, near Halifax… all gone. Forgotten. Demolished. As nature takes its course.

I know exactly where I’m from / And I know where I will go

I’m born of raindrops poured from cloud / And I run to the river below (I know)

I run run run run to the river below

STEVE: Ladies and gentlemen, we’re getting towards the end of our time with you this evening, so let’s bring our story up to date. To this post-industrial era. In these decades following the Revolutionary Reign of the Divine Margaret, the people of Airedale don’t actually make anything anymore. Somebody, somewhere, realised it was cheaper to make the mohair jumpers nearer to where the llamas are, instead of bringing their wool all the way here to be sorted, scoured, combed and woven. We don’t make things any more, but we do still sell ‘em, and these days, the riverside land-grabs are all about supermarkets. Former mill sites are now prime brownfield targets for the builders of big metal boxes with big glass windows – big metal boxes to be staffed at minimum wage, on zero hour contracts, by the children and grandchildren of millworkers.

In Shipley, there was recently a three-way dogfight over the right to build a new supermarket. One developer was looking to build a Tescos on the Airedale Mills site right next to the main river at Baildon Bridge. Another developer was proposing a new Morrisons store on the banks of Bradford Beck, just across the valley from Shipley station. But Bradford Council’s officers, in their wisdom, sparked a storm of protest by endorsing a third proposal – for a supermarket not far from Shipley’s existing Asda. This proposal, too, involved a site right next to Bradford Beck… a site currently occupied by the Crossley Evans scrap metal facility…

Save Our Scrapyard

There are very few songs about Shipley / Fact I’m struggling to find even one

So it’s time to immortalize Shipley (quickly) / In this jolly little protest song:

For down by Shipley station / There’s a wave of indignation

Shipley’s up in arms at published plans / To replace its stunning scrapyard

With another ruddy supermarket / Folks are raising banners, singing chants

(Chorus:)

Save Our Scrapyard, it must not be destroyed

Save Our Scrapyard, it’s Shipley’s pride and joy

Let’s fight to keep it / It’s iconic, it’s unique it

Stands as a symbol of our age / Let’s go ballistic

Shout until it’s Grade One listed / Shipley burghers man the barricades

(Chorus)

It’s got / Railings, palings, cisterns, pistons

Clapped out central-heating systems / Looms exhumed from textile mills

Locos, engines, tenders, rails / Pylons, printing presses, lots of

Telephone and pillar-boxes / Mangled metal, twisted tubes

Motor-cars crushed into cubes / Derricks, girders, pithead pulleys

Seized-up supermarket-trolleys / All that’s wrecked and that rusts

All that’s chucked away by us

Let’s fight to keep it…… (second verse repeat; then Chorus)

Save Our Scrapyard, this is an SOS

Save Our Scrapyard, this is Shipley in distress

Save Our Scrapyard, it’s Shipley’s sculpture park

If Shipley were in London this would be a work of art

Save Our Scrapyard, it must not be destroyed

Save Our Scrapyard, it’s Shipley’s pride and joy!

STEVE: The scrapyard, you will be pleased to hear, was saved. Bradford councillors rejected their officers’ recommendation, and opted for the Morrisons scheme instead. But since this one involved building over land that currently grows wild — and whose grasses attract rare butterfly species – another protest was sparked, and a rash of graffiti sprang up along Shipley’s canal banks:

STOP MORRISONS KILLING RARE MARBLED WHITE BUTTERFLY IN SHIPLEY

STOP MORRISONS KILLING RARE MARBLED WHITE BUTTERFLY IN SHIPLEY

MAN IS BORN FREE BUT IS EVERYWHERE IN CHAIN STORES

These legends are stencilled in black onto patches of vivid, Morrisons-yellow paint, alongside images of the threatened butterflies. If you look carefully, you can see that somebody – perhaps Bradford Council – has attempted to paint over the offending text in a slightly different yellow, while leaving the decorative butterflies to beautify the dull grey walls. Not to be silenced, the protestors have returned to reapply the stencils.

Meanwhile, this impromptu canalbank gallery has been lent celebrity glitter by the appearance of other images apparently stencilled by Banksy – the world’s most famous graffiti artist. A single image recurs three times in the vicinity of Shipley Wharf and Gallows Bridge – the image of a young girl clutching a black flying bomb as if it is a beloved teddy bear. She is waiting for the future to blow up in her face.

When we look at our canals and rivers, what do we see? Do we see post-industrial neglect and future decline? Do we see opportunities for commercial regeneration? Do we look at waterways and their banksides as resources to be exploited? Or do we see them as speaking to a sense of place… To a kind of belonging?

Ladies and gentlemen, we’re going to close this evening with Eddie’s song, Bradford Beck. It’s a kind of protest song. For most of its journey through Bradford, the Beck runs underground. The Victorians arched it over. Treated it as a sewer. Even those sections that remain above ground were for many years policed with warning signs: “Danger: Contaminated Water”. A couple of years ago, though, a new voluntary group called the Friends of Bradford’s Becks went round all those signs pasting new wording over the old. They now read, quite simply, “This is Bradford Beck.”

It’s in the very nature of this green and pleasant land

You’re bound to find a watercourse runs very close at hand

Our rivers and canals are full of good old English rain

But if you come to Bradford you will look for one in vain

From somewhere up near Allerton I tumble down to town

But the pleasure ends near Four Lane Ends when I’m shoved underground

And what goes on as I flow on nobody gives a damn

For instead of being a chuckling stream, a sewer’s what I am

My name is Bradford Beck / If you wonder what the heck I’m doing singing this song

It’s ’cos I have to roll along incognito / Beneath the city streets with no credibility

Despised, unrecognised – set me free!

As 200 years of soot and smog and smoke come to a close

Say “waterside” and everyone says “We got one o’ those”

Besides the likes of Tyneside, Norwich, Leeds or Birmingham

Every tin-pot town pretends it’s Venice or it’s Amsterdam

But I have no illusions nor ambition to pretend

To challenge the charisma of the Severn or the Thames

But I have been anonymized as long as I can bear

It’s time to give me credit, give me sky and give me air

My name is Bradford Beck / Still flowing undetected under pavement and road

But history will show I’m a survivor

For umpteen thousand years I’ve made my way to to’t River Aire (just down there…)

For thousands more, I’m sure – I’ll still be there

But now’s the time to help me shine and start to play a role

By sharing people’s daylight, not hiding in a hole

No longer a joke with Bradford folk, but giving of my best

With trout and tiddlers, weeping willows, ducks and water-cress

But I’m culverted and tunnelled out of sight and out of mind

And when I briefly re-emerge I’m verged with warning signs

The cultures that can thrive in me might make you feel unwell

My name might not be Styx but I am very close to hell

My name is Bradford Beck / It’s time for resurrection from this rat-ridden cave

Time for me to save my reputation

I’m real West Yorkshire water and I ought to be clean

Be treasured, be a pleasure – and be seen

(Repeat first Chorus)

END.