Just this morning, Prime Minister Theresa May announced plans to write off “tens of billions of pounds of housing associations’ debt”. The idea is that, if those organisations don’t have to service these debts, their finances will be freed up to actually build more social housing — and so address the chronic shortage of affordable homes. It’s a response, of sorts, to the UK’s much-debated housing crisis. But will such generosity in debt relief be passed on by the housing associations to the tenants who owe them…? That’s a question that also needs asking, when so many people are facing potential eviction from their homes. Not least in Bradford…

This brings me back to Jenni M. and her family. I wasn’t going to blog about them again, because this is not a story about water (which this blog-site is supposed to be concerned with), and also because discussing one family’s financial problems in a public forum like this seemed too personal, too intrusive. But… the story was already public, because of a crowd-funding campaign I ran two weeks ago on justgiving.com … and then this week I got a call from BBC Radio 5 Live… and then an email from someone at a TV production company too… and I realised that the story had attracted national interest, never mind just local. So I needed to find a way to reflect on it.

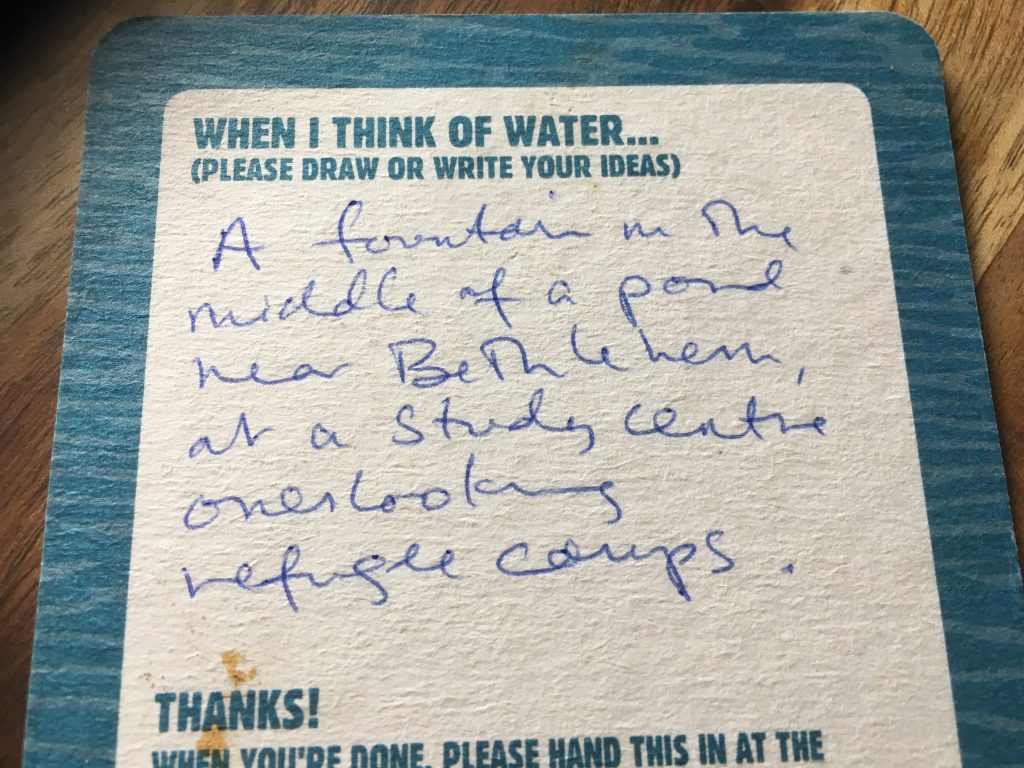

This is Jenni and her son, Dylan, in the picture I used on Just Giving this month. The snap was actually taken last year, near their home in Bingley, and right next to the Leeds-Liverpool Canal. When this picture was taken, we had just finished filming material for a short documentary, High Rise Damp, which looks at the family’s housing situation on the Crosley Wood estate (three concrete tower blocks from the 1960s, which are long past their use-by date). Jenni agreed to take part in the film on the understanding that this was not a film about her so much as it was a film about people like her. The idea was to tell a story that, while necessarily personal, might be understood as being representative of many similar stories…

In the film, Jenni mentions getting into rent arrears with her housing association, Incommunities, at a time when she was having to take a lot of unpaid time off work because Dylan was sick with asthma — a condition that doctors said was very likely caused, or at least exacerbated, by the damp conditions in their flat. As a consequence of her mentioning this, public screenings of this film have led on more than one occasion to individual spectators offering to help pay off some of the family’s debt. Jenni, however, while grateful for such generosity, has resisted such offers on the grounds that this was — as I said — not just about her. Why should she benefit personally when so many others are in similar need?

Jenni’s admirable reluctance to take personal advantage of the situation is just one of the reasons why I like her so much. But this summer the family’s financial situation took a turn for the worse (for reasons too personal and non-relevant to discuss here), so that their careful attempts to manage their outstanding debt, while also paying their current rent due, was thrown off kilter. As a consequence, their housing association Incommunities began threatening eviction, and the family was eventually informed that the bailiffs would be coming to repossess their flat on Tuesday 7th November, unless they could come up with a big chunk of the money they owed. To be fair to Incommunities, they did respond to Jenni’s request for mercy: in the end, their demand was for a substantial portion of the debt, rather than the whole thing, to be paid off if eviction was to be avoided. But that offer left Jenni’s family with less than a week to find £1700, and they simply had no idea where they were going to find such a sum. Clutching at straws, I asked Jenni if I should try “going public” through a crowd-funding campaign.

We were both very wary about this idea, for obvious reasons. Jenni would be putting her family in the public eye as people who owed a substantial amount of money — and we were concerned that this might invite negative reactions. And why, given that so many other families are facing similar situations at present, would anyone think this particular family was worth helping? Jenni was as sceptical as I was about whether we would achieve anything, but as she said, she just didn’t have any other options left.

So… I set up a Just Giving page on the morning of Thursday 2nd November, with no idea whether we’d get anywhere. I put the link on my personal Facebook page, shared it on the Multi-Story Water Facebook page, and tagged a few people I knew who had seen the film, in the hope that they would feel inclined to donate. I’m no social media native (don’t even start me on Twitter…) so I privately felt that this was probably far too little, far too late. But by some miracle of viral sharing, the donations began to roll in that morning, surged a bit at lunchtime, tailed off during the afternoon, and then accelerated quickly again after work… We hit our £1700 target on that first day of the appeal, by around mid-evening…

Amazed and humbled, I posted a message thanking everyone who had donated, and mentioning that — if anyone else still wanted to donate — then the extra would all go to further defraying the family’s rent arrears. And over the next few days, sure enough, the total sum continued to tick up. By Tuesday — the day of the scheduled eviction — the total amount given had topped just over £2,200 (where it has stayed since).

Amazed and humbled, I posted a message thanking everyone who had donated, and mentioning that — if anyone else still wanted to donate — then the extra would all go to further defraying the family’s rent arrears. And over the next few days, sure enough, the total sum continued to tick up. By Tuesday — the day of the scheduled eviction — the total amount given had topped just over £2,200 (where it has stayed since).

By then, of course, the eviction had been called off because we had been able to pay off the required sum. Jenni and her family — completely gobsmacked by the public response — breathed an enormous sigh of relief and sent out prayers and thanks to everyone who had donated:

“I cant believe all the wonderful people out there willing to help us. It was never my intention but we are so desperate it was the only other option. I have no words we can’t thank you and everyone enough, Dylan has a smile on his face and that’s priceless x. I want everyone to know how much we appreciate their help and support, some of the comments have brought tears to my eyes x”

So why did so many people support this? There were 98 separate donors in the end, most of whom did not know Jenni or her family at all. The statistics on the Just Giving site say a lot: after being shared 80 times on that first day alone, the page was viewed over 2000 times… So it was enough that around 1 in 20 of the people who looked at the story decided to donate… And that’s how these things work!

“Saw the film a few months ago and I’m really glad you’re fundraising. I wanted to help, and now I can (at least a bit!) Good luck everyone, more people are on your side than you’ve ever met.”

Interestingly, among those who did get onboard with the campaign, it actually became a bit of a “thing” that Thursday. I followed some Facebook feeds where people were reporting to each other that they had donated, and were updating each other on the rising total, with considerable good humour and something approaching excitement! As one friend of a friend commented, “this thread has made my day!” It’s really a win-win when people can be entertained by giving money to somebody else!

But what was also very clear from the comments posted was that people saw this as a symbolic campaign. It was, again, not just about Jenni’s family. They had simply become a publicly-identified example of a problem that many people were aware of but didn’t know how to do anything about. So given the chance to do something, people did… “We shouldn’t have to do this“, wrote one donor, while doing it, “but I can’t stand by and let this happen.”

Other comments suggested an awareness of the stark irony that donors were being asked to help Jenni and her family to stay in less than ideal living conditions:

“I would love to see them have enough to rehouse themselves somewhere healthier and happier. Housing in this country is appalling. Best wishes xx”

Of course part of the Catch 22 that families like Jenni’s face is that it is very difficult to get anywhere else to live if you cannot get a good reference from your previous landlord. And that won’t happen if you owe them money… So let’s hope that, with a big chunk of their debt now cleared, Jenni and her family are indeed closer to be able to rehouse themselves somewhere better.

Anyway, as I said at the outset, I wasn’t going to blog about this. But then a couple of days ago, I picked up a phone message from someone at Radio 5 Live, who had read about the crowd-funding and wanted to know if Jenni and Dylan might be willing to talk on the radio… They were looking for personal stories to illustrate the wider problem of the housing crisis.

I called Jenni and discussed this with her, but she – quite understandably – said that she didn’t want to be on the radio. She had gone public because she needed to, but she didn’t have any wish to become a public figure. She was, she said, perfectly happy for me to speak on the family’s behalf if the radio people were good with that, because she knew I would try to direct the story back to the general problem and away from the personal specifics. One thing that both of us have found is that some people can get unduly nosey about personal specifics, once a story like this is out there…

In the event, nothing happened with the BBC, because when I called them back the next day, it turned out that they’d already covered housing on that morning’s breakfast show… (after leaving me a message at 4.30pm the previous afternoon… clearly I’m not wired for radio schedules!) I suspect they wouldn’t have pursued this story anyway, without Jenni herself being willing to speak on air, but the person I talked to did ask me how she was, and seemed genuinely pleased when I confirmed that the eviction had been called off…

You see, people do care about people. And actually, I do believe that many people who work for housing associations also care about people. This shouldn’t become an “us versus them” situation, because some of the problems here are systemic and are beyond the power of any one organisation to address (I tried to discuss some of these complexities in a 3-part blog I wrote in August). So the real question is how to turn the evident public concern about these issues into a movement for real political change. Because this is not just a story about individual families.

***

I have to stress again that I’m no expert on these issues, but I do think — as I indicated at the start of this blog — that it’s not enough simply for this Conservative government to throw money at housing associations and their balance sheets. That’s no guarantee that such money will really be used in a way that helps those most in need, unless clearer policy guidance is also put in place.

That seems to be the thought underlying the Labour Party’s decision this week to launch a petition — addressed to the Prime Minister — demanding that new regulations are put in place to ensure social housing be made safer for all residents. (This is the link, in case you want to sign it!) “Thousands of families are living in high-rise properties in the UK“, the petition statement begins: “Nearly all of these homes do not have adequate safety systems.”

It must be said that there’s no actual evidence on the petition to back up this claim (which is of course inspired by the ongoing controversy about the Grenfell tower fire in London). But in the case of Bradford, the assertion raises a specific question for Incommunities… When Jenni and I met with Chief Executive Geraldine Howley on August 11th, she told us that an independent fire safety audit of Bradford’s tower blocks had been commissioned from Savills. This was scheduled to begin the following week, on August 18th. It must, presumably, have been completed by now, so Incommunities should have detailed information on whether or not their tower blocks have adequate safety systems. However, I’ve searched the Incommunities website, and also the Telegraph and Argus website for reporting on this topic, and I can’t find any evidence that the findings of that Savills inspection have been made public. So where are they?

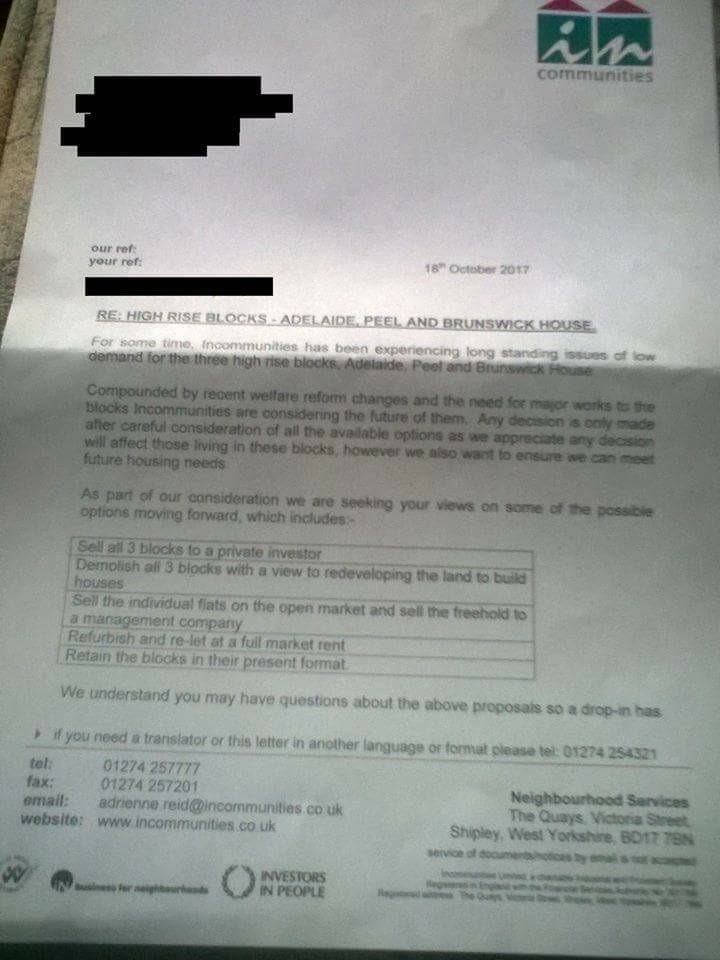

If they have been published, and I’ve missed it somehow, and everything is fine, then that’s great. But the communication that residents at Crosley Wood have been receiving recently has not been about safety, it’s been about these tower blocks possibly being sold or demolished by 2019, and the residents being relocated (see my last blog). The stated reason for this future planning is that the estate is now economically unviable, because of a lack of demand to live there… And maybe that’s really all there is to it. But as long as pertinent information remains (apparently) unpublished, then people are bound to worry that there’s something they are not being told.

People who live in tower blocks deserve to know the truth about the conditions they’re living in. So if the Savills report has not yet been made public, then maybe it’s time that it was. Fire safety has become a political issue since Grenfell tower, but it’s also a very immediate, personal issue for residents…