Like many people, I’ve spent a lot of time this week trying to make sense of the chaotic whirlwind that has been President Donald Trump’s first week in office. Events in Washington don’t normally have much to do with the waterways and communities of Shipley (this blog’s usual subject matter), but there was something about the Women’s March held last Saturday in Shipley town centre — in protest at Trump’s inauguration — that resonated deeply for me. Let me try to explain why.

Like many people, I’ve spent a lot of time this week trying to make sense of the chaotic whirlwind that has been President Donald Trump’s first week in office. Events in Washington don’t normally have much to do with the waterways and communities of Shipley (this blog’s usual subject matter), but there was something about the Women’s March held last Saturday in Shipley town centre — in protest at Trump’s inauguration — that resonated deeply for me. Let me try to explain why.

The march in Shipley was, of course, one of many held all around the world. But unlike most of the other places where this happened, Shipley is not a major city. It’s not London or Manchester or Glasgow or even Leeds. It’s a small, former mill town, and the decision of some of its citizens to march was curious enough to attract journalistic comment as far away as India. The specific, local incentive for the action was a kind of subsidiary protest against the local Conservative MP, Philip Davies, who has stated that he would have voted for Donald Trump “in a heartbeat”. But it’s not just his liking for Trump that has antagonised Shipley’s self-proclaimed “Feminist Zealots” (their name is an ironic dig at Davies’s derogatory terminology); it’s their sense that he seems similarly reluctant to treat women as equals. Davies may not have been recorded boasting about grabbing small felines, but his membership of Parliament’s Equalities and Diversity Committee is — as even he would likely admit — about as natural a fit as asking Nigel Farage to join the European Commission.

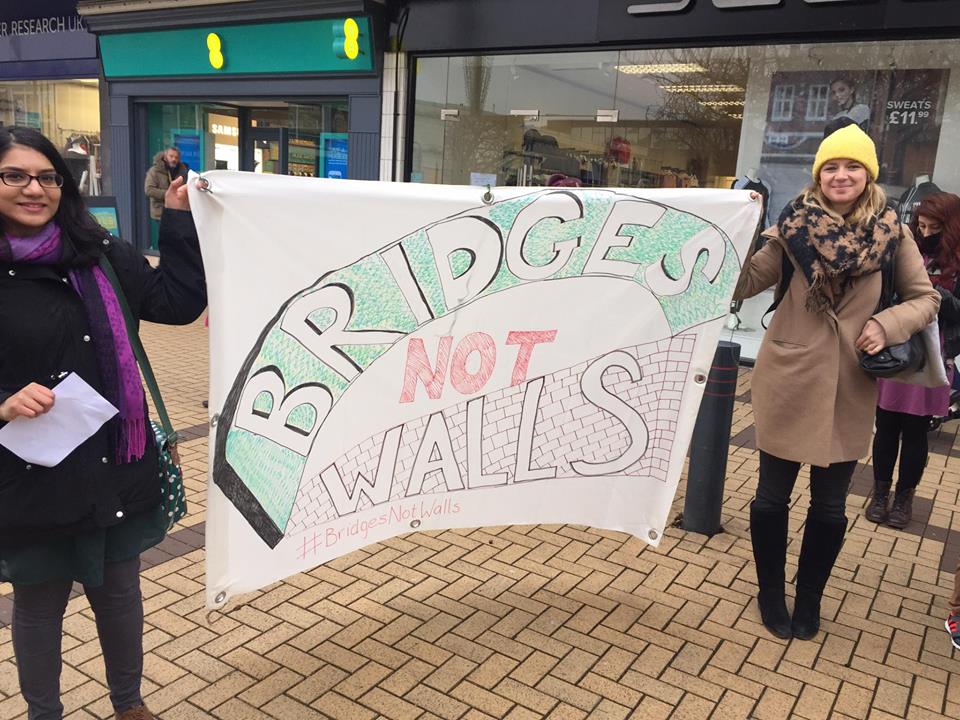

I will nail my colours to the mast and say that I whole-heartedly support the Feminist Zealots of Shipley — from whose previously ‘secret’ Facebook feed I have nicked these pictures of the march (with apologies to the photographers). But I also think it’s important to say that Philip Davies is not a man simply to be rubbished and ridiculed (despite the best efforts of, say, comedian Russell Howard). Whatever one thinks of his politics, it’s hard to deny that he is also a hard-working constituency MP who is quite remarkably responsive to the needs of constituents, regardless of who they vote for, or indeed what sex they are. I’ve lost track of the number of stories I’ve heard from local people of how he has helped them out with pressing problems to do with housing, local services, etc. Davies has earned the gratitude and respect of many, which is no doubt a big part of the reason he gets re-elected. So it was great to see that even the protest against him was voiced in a creative, generous spirit, rather than in the kind of divisive, aggressive language that Donald Trump himself has become known for:

I will nail my colours to the mast and say that I whole-heartedly support the Feminist Zealots of Shipley — from whose previously ‘secret’ Facebook feed I have nicked these pictures of the march (with apologies to the photographers). But I also think it’s important to say that Philip Davies is not a man simply to be rubbished and ridiculed (despite the best efforts of, say, comedian Russell Howard). Whatever one thinks of his politics, it’s hard to deny that he is also a hard-working constituency MP who is quite remarkably responsive to the needs of constituents, regardless of who they vote for, or indeed what sex they are. I’ve lost track of the number of stories I’ve heard from local people of how he has helped them out with pressing problems to do with housing, local services, etc. Davies has earned the gratitude and respect of many, which is no doubt a big part of the reason he gets re-elected. So it was great to see that even the protest against him was voiced in a creative, generous spirit, rather than in the kind of divisive, aggressive language that Donald Trump himself has become known for:

This slogan — “Bridges Not Walls” — recurred on a number of placards on the march, and exemplified the spirit of wanting to build and heal, rather than divide and antagonise. It’s also a gift to your local water-blogger, because of course Shipley has no shortage of bridges. Off the top of my head, I count seven road and footbridges across the canal between Dockfield and Hirst Wood (not including the lock gates, which you can also walk across), and a further four across the River Aire. (Of course the canal even takes a bridge of its own over Bradford Beck at one point, just to underline my point…) In short, in the Shipley area, we’re pretty good at finding our way over sometimes troubled waters. So maybe there are even bridges to be built between Philip Davies and his opponents? Before that begins to sound tritely optimistic, let’s take a closer look at one particular bridge…

This is Victoria Street in the foreground, ramping up to the left of the picture as it starts to bridge the Leeds-Liverpool Canal in central Shipley. (The distinctive chimney of Salts Mill is in the distance, to the west.) One the right of the image, standing to one side of the canal, is the headquarters of In Communities, Bradford’s social housing authority. (I’ll come back to them in a minute.) On the left of the picture — and directly across the canal — is the distinctive red-brick structure of the former Leeds-Liverpool Canal Company warehouse. This pairing of buildings, old and new, facing each other across the water, sums up quite a lot about the state of modern Shipley. Let’s look first at the warehouse…

This is Victoria Street in the foreground, ramping up to the left of the picture as it starts to bridge the Leeds-Liverpool Canal in central Shipley. (The distinctive chimney of Salts Mill is in the distance, to the west.) One the right of the image, standing to one side of the canal, is the headquarters of In Communities, Bradford’s social housing authority. (I’ll come back to them in a minute.) On the left of the picture — and directly across the canal — is the distinctive red-brick structure of the former Leeds-Liverpool Canal Company warehouse. This pairing of buildings, old and new, facing each other across the water, sums up quite a lot about the state of modern Shipley. Let’s look first at the warehouse…

If you were looking to find local examples of what President Trump was speaking about in his ominous inauguration speech — those “rusted out factories scattered like tombstones across the landscape of our nation” — well, this would be as good a place as any to start. Sure, it’s a warehouse, not a factory, but this rather beautiful edifice (which my friend Eddie Lawler has playfully earmarked as the HQ for his imaginary “University of Saltaire”) has been left to go to rack and ruin in recent decades. It’s one of many sadly neglected canalside structures, which has never been retrieved and repurposed for any “post-industrial” service industry. But the question is, what would a Trump (what would a Davies?) propose to do to remedy the situation?

The answer promoted by most mainstream politicians, of either hue, in the UK and US over the last 30 years has been to trust the market. Private enterprise, we are told, will deliver improvements to all our lives… Well, perhaps it will in some places, but the canal company building is still there, crumbling, and last month it was raided by police officers charged with shutting down an unregulated private enterprise…

As reported by the Telegraph and Argus , this was not the first time that the building has been squatted for the purpose of growing industrial quantities of cannabis…

The spirit of free enterprise has always been about serving yourself first, even if that involves stretching the law. It’s useful for some things, but it’s not going to save the crumbling infrastructure of Yorkshire’s former mill towns, let alone the American “rustbelt” states that swung victory for Trump. And the new President, who knows a thing or two about free enterprise, knows there’s no business incentive for rebuilding in depressed areas. (Where’s the profit in that?) So instead, he is promising the biggest federal infrastructure programme since FDR’s New Deal in the 1930s. Donald the Builder wants to make more than his signature golden towers. His plans will, he promises, put thousands of ordinary Americans back in work, and it’s these promises that got him the votes he needed in Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania to win the election.

The spirit of free enterprise has always been about serving yourself first, even if that involves stretching the law. It’s useful for some things, but it’s not going to save the crumbling infrastructure of Yorkshire’s former mill towns, let alone the American “rustbelt” states that swung victory for Trump. And the new President, who knows a thing or two about free enterprise, knows there’s no business incentive for rebuilding in depressed areas. (Where’s the profit in that?) So instead, he is promising the biggest federal infrastructure programme since FDR’s New Deal in the 1930s. Donald the Builder wants to make more than his signature golden towers. His plans will, he promises, put thousands of ordinary Americans back in work, and it’s these promises that got him the votes he needed in Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania to win the election.

The question is, who is going to pay for all this? Because much as we’ve all got tired of mainstream politicians who seem only to represent vested interests (hence the Trump rallying cry to “drain the swamp!”), we’ve also got used to not having to pay too much in taxes. Hence Trump’s determination to make Mexicans, not Americans, pay for his most controversial infrastructure project — the mooted wall on America’s southern border (which, of course, the “Bridges Not Walls” slogan refers to). Well, good luck with that, Donald. So far the Mexicans don’t seem too impressed by your negotiation tactics.

But enough about America. Let’s get back to Shipley. Where the appeal of Philip Davies to local voters is perhaps not dissimilar to the appeal of Donald Trump. His slogan is “Your Interests, Not Self Interest”. And as I mentioned, Mr. Davies does seem to do a fair job of helping people out with their immediate difficulties, by banging heads together where he can. And yet… in this era of small-ish government and low-ish taxes, there’s little prospect of the local infrastructure being rebuilt any time soon.

For me, this realisation has become particularly apparent this last month thanks to some striking bits of local history. Paul Barrett at Kirkgate Centre recently circulated this link to Operation Progress — a 1957 documentary film, on the British Film Institute’s web player, which shows the demolition of some of Shipley’s insanitary old back-to-back houses, and the building of the spanking new council housing estates along Coach Road. You get an amazing sense, watching this film, of just how exciting and progressive it seemed at the time to build these solid new homes in green spaces on the Baildon side of the river — transplanting people from the dark, crowded streets so many had been living in before. This was “operation progress”, and it was masterminded not by private enterprise or indeed by central government, but by Shipley Urban District Council. They had a masterplan, and they carried it out, and in many ways we’re still living with the landscape they created in the 1950s. Partly because there’s been no comparable attempt at regeneration since…

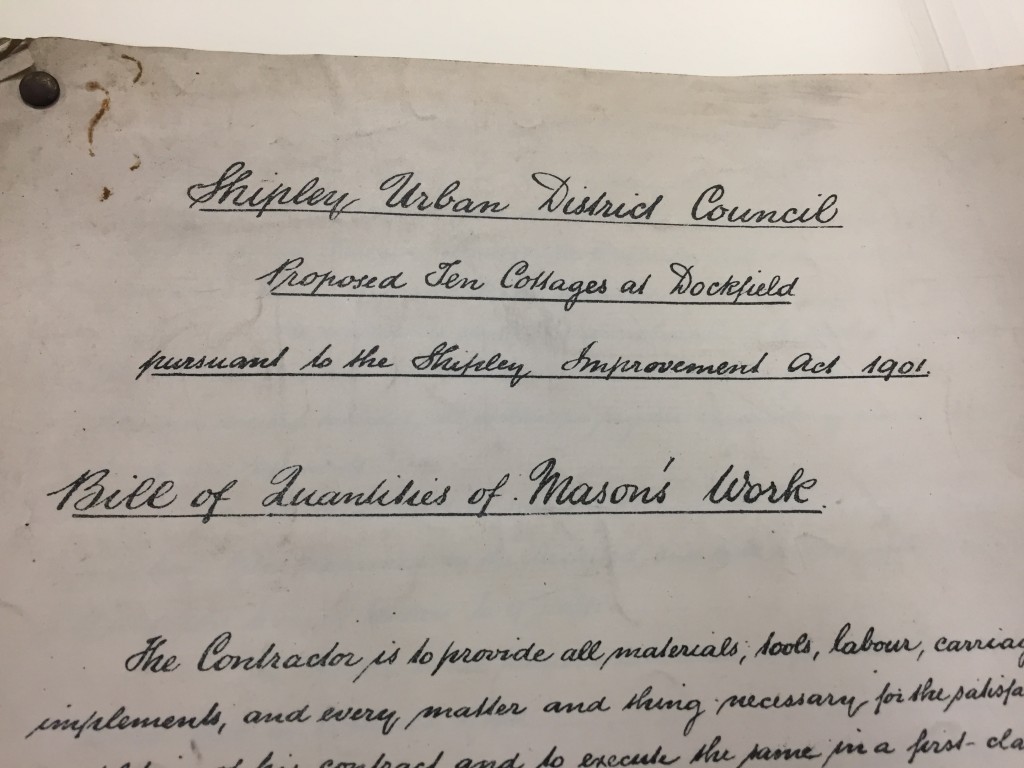

I’ve also been actively researching the history of Shipley’s Dockfield area this month (see also my last blog), and one of the striking things I’ve discovered is that here, too, it was Shipley Urban District Council that made all the difference. Not in the 1950s, but half a century earlier, when SUDC had a masterplan called the “Shipley Improvement Act of 1901”.

Up til then, Dockfield had basically been the wild west (or rather east) — an area dominated by a few largely unregulated textile mills, with the only road access going under the railway via Dock Lane. The lane was in a shocking state of disrepair because the mill owners didn’t want the responsibility or cost of maintaining it. But then SUDC built Dockfield Road as a modern road link from the main Otley Road. And alongside Dockfield Road, SUDC built the row of terraced housing that still stand there. And at right angles to Dockfield Road, they also built the homes along Dockfield Terrace. Council houses all. And they made them solidly, from stone, with then-state-of-the-art plumbing and heating systems.

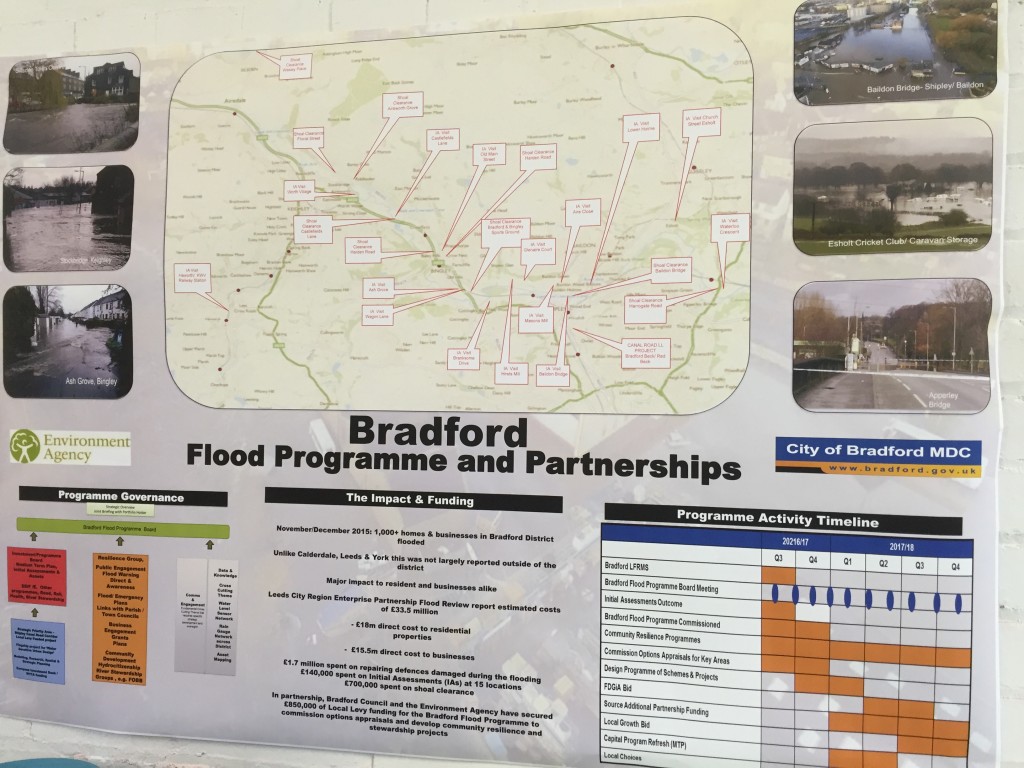

And at the same time they built a water treatment works in Dockfield, as the outfall to a brand new sewage main running west to east, the length of Shipley. Because decent sanitation is a basic health requirement. But left to its own devices, free enterprise was never going to provide it.

All of which brings me back to In Communities. Remember them? Opposite the weed warehouse? It oversees what’s left of Shipley’s council housing stock. Of course, ever since Mrs. Thatcher introduced the right to buy in the 1980s, most council housing in the area — whether along Coach Road (c.1957) or in Dockfield (c.1908) has been sold into private ownership. There’s not much stock left, because there’s been no new drive for social house-building. Because — we’re always told — we can’t afford it. And to judge from the Comments on the InCommunities facebook page (where the average ‘star grading’ out of 5 is 2.2), the condition of much of the remaining stock is poor, and too little care is being taken about the welfare of those people having to live in them. In fact, I even made a film about this recently. But that’s another story.

My point is, if you look around Shipley, it’s easy to see why people here might — given the opportunity — vote for Donald Trump. Whether “in a heartbeat”, or just in the forlorn hope that it might change something. But my point is also that what we really need is properly resourced, properly led local government, with a new vision for the town’s future.

Is it too much to hope that we might build a bridge, on this basis, between Philip Davies and his detractors?

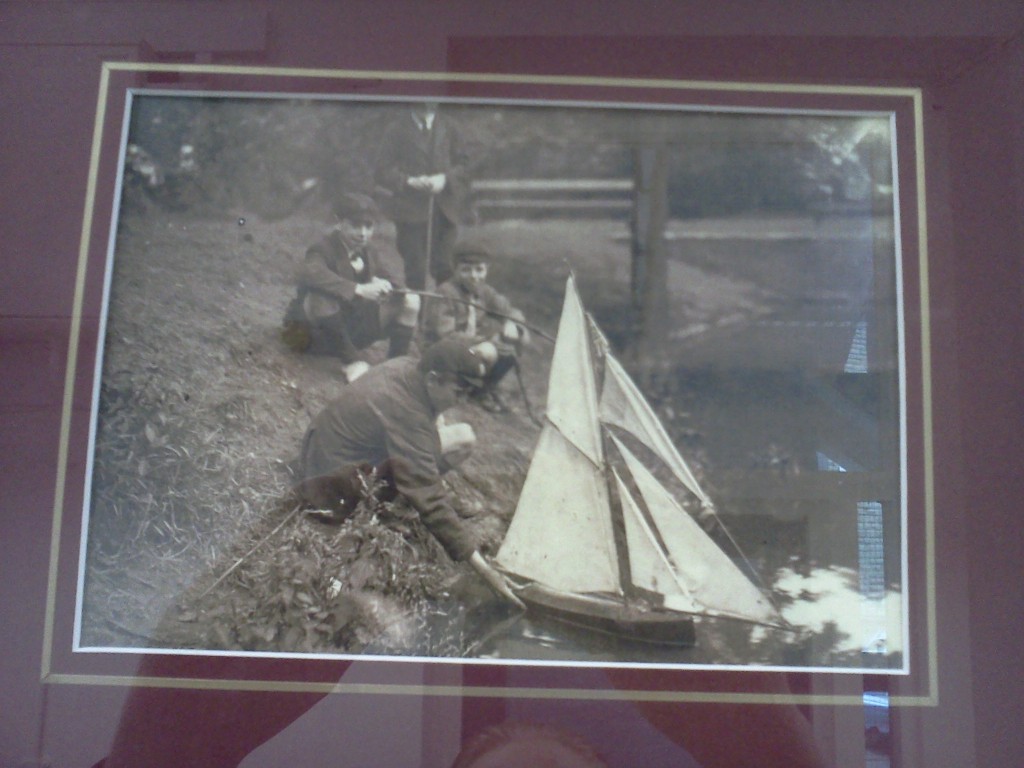

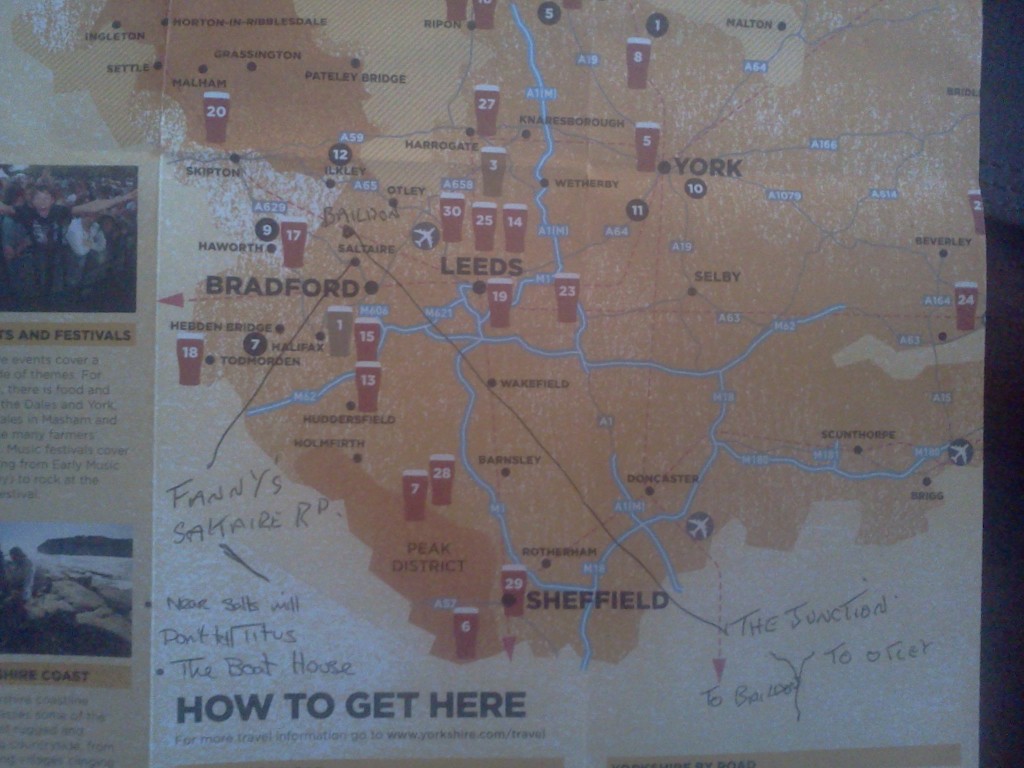

This is Dockfield’s Junction Bridge. Built in 1774 to allow horses to cross from the towpath of the Leeds-Liverpool Canal to the connecting towpath of the Bradford Canal. This is the junction – and the bridge – at the heart of Bradford’s early industrial expansion. Behind the bridge, Junction House — also built in 1774 — continues to fall into chronic disrepair…