OK. So where to begin?

“In the beginning,” we are told, “God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form, and void; and darkness was on the face of the deep. And . . . God said, ‘Let there be light’; and there was light.” (Genesis 1: 1-3)

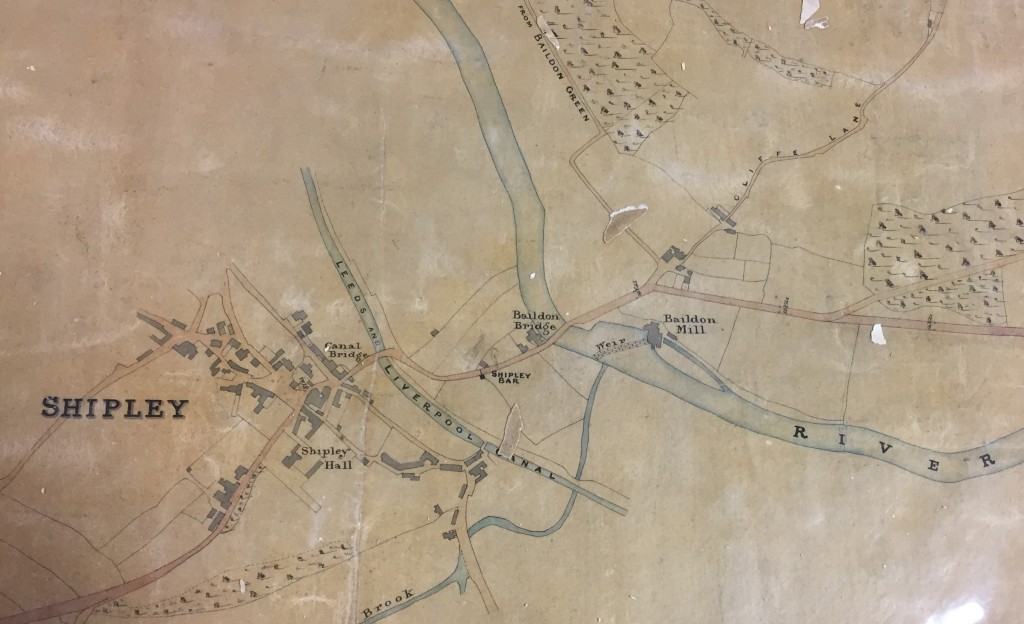

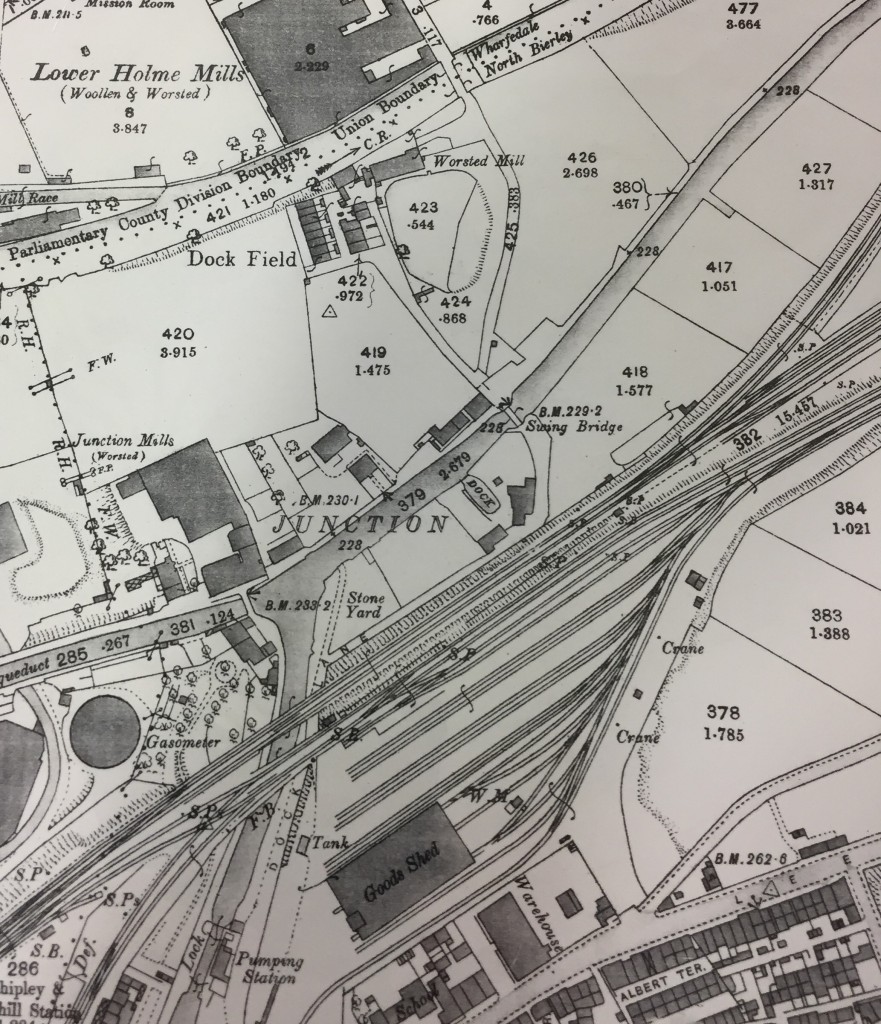

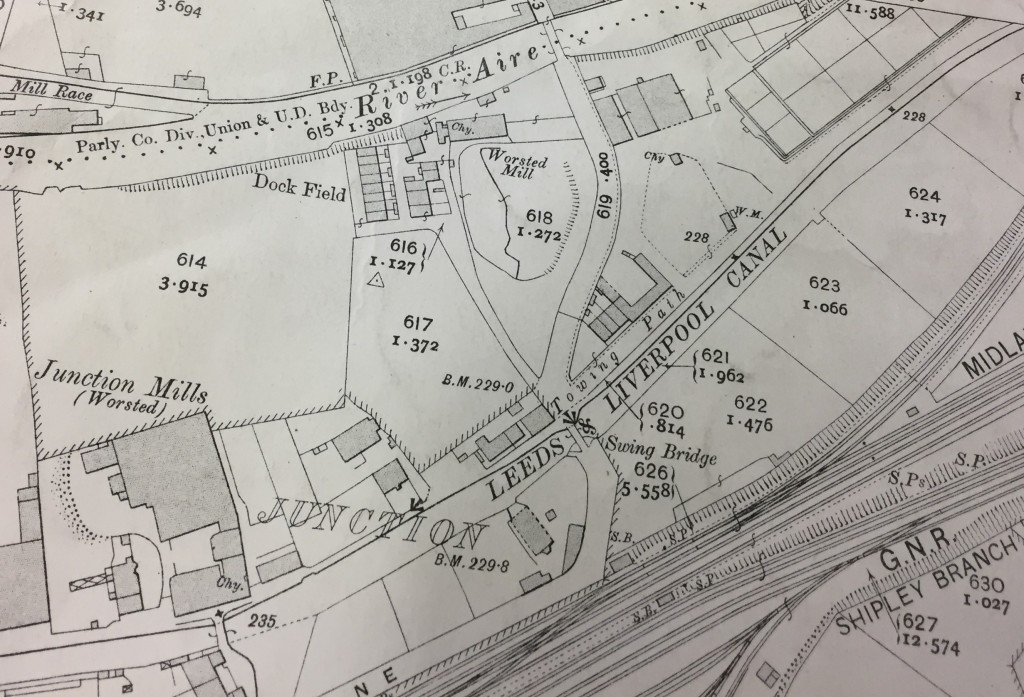

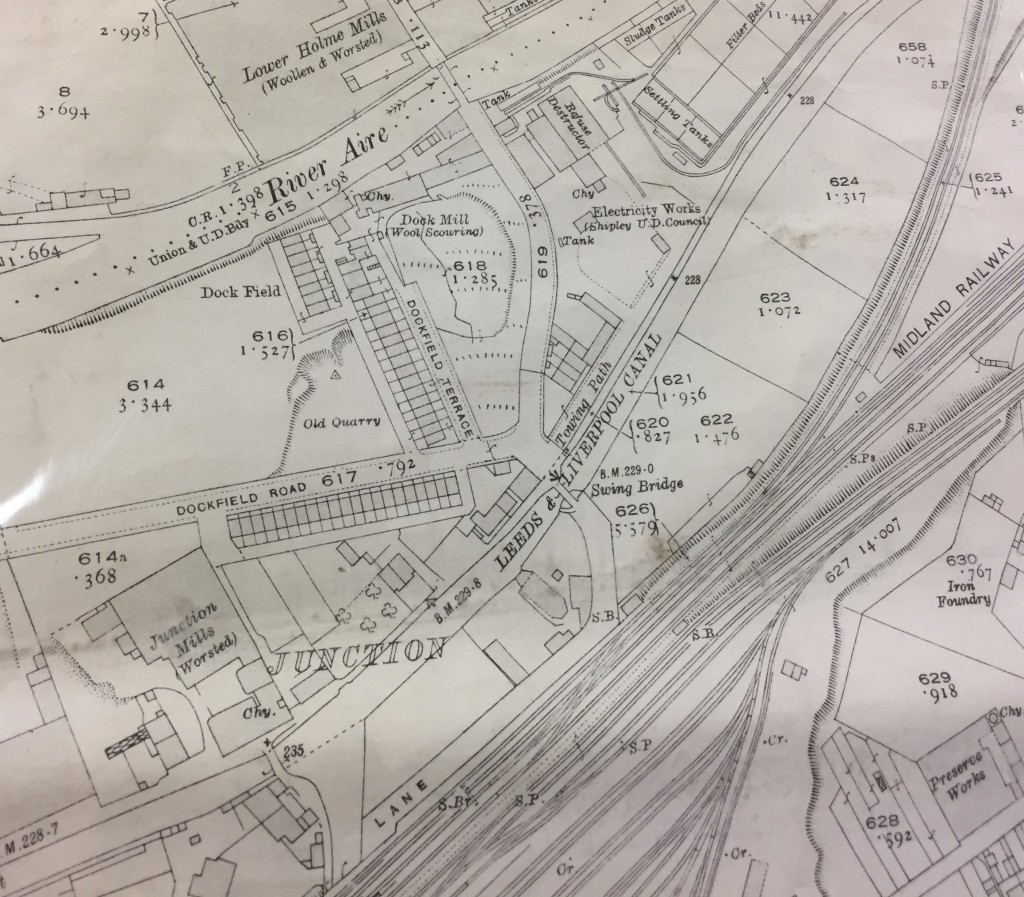

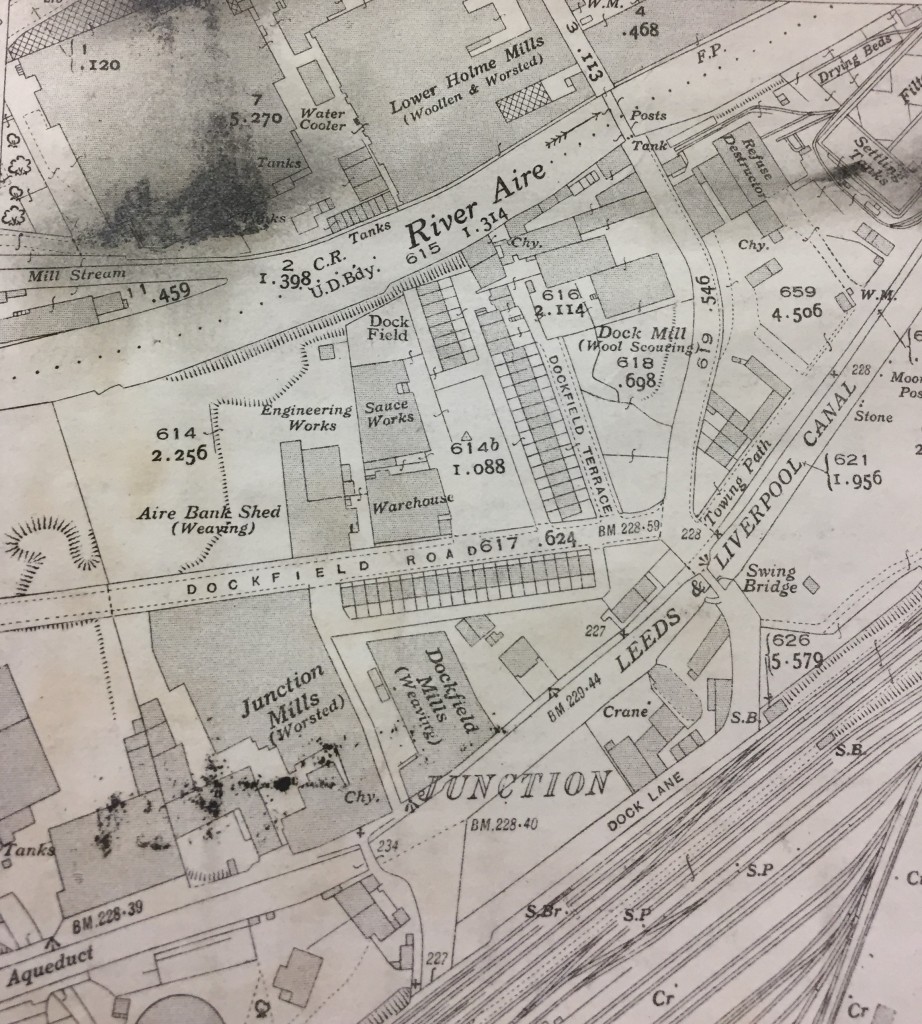

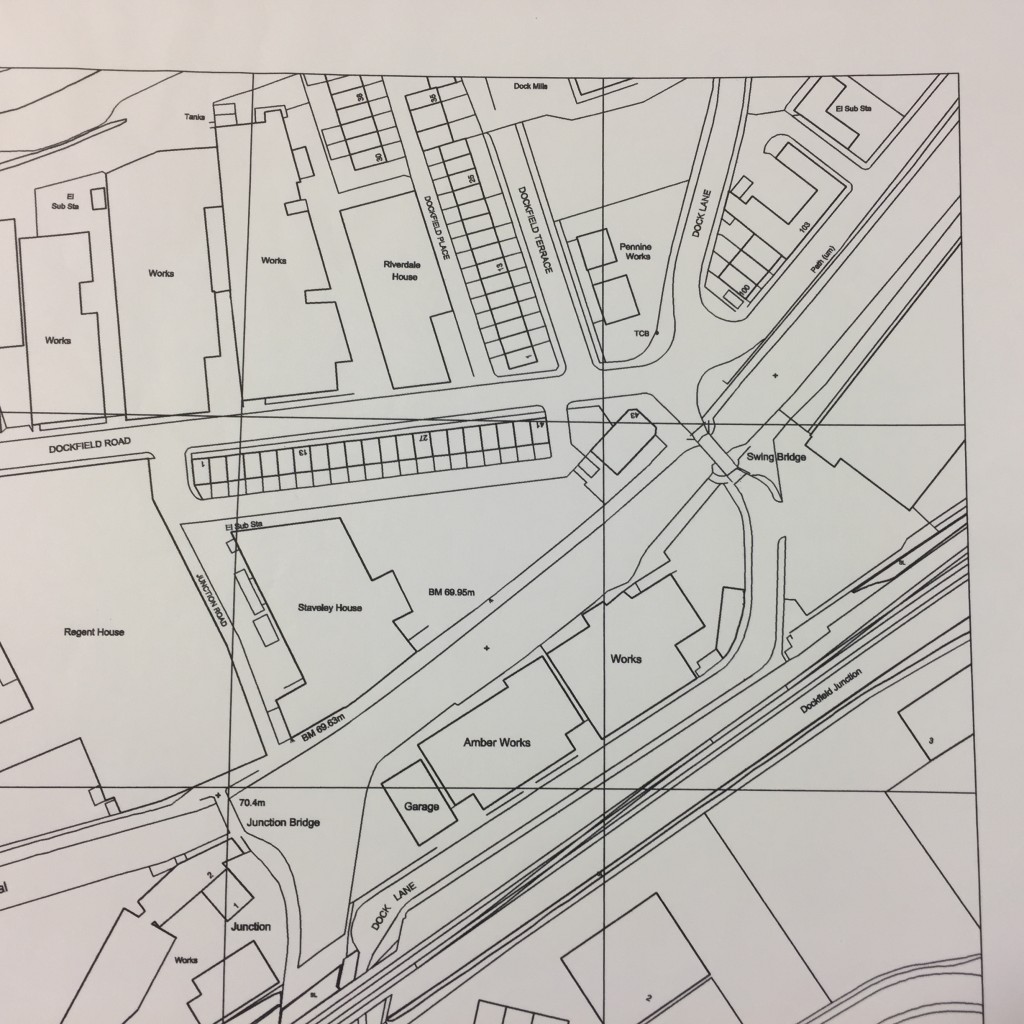

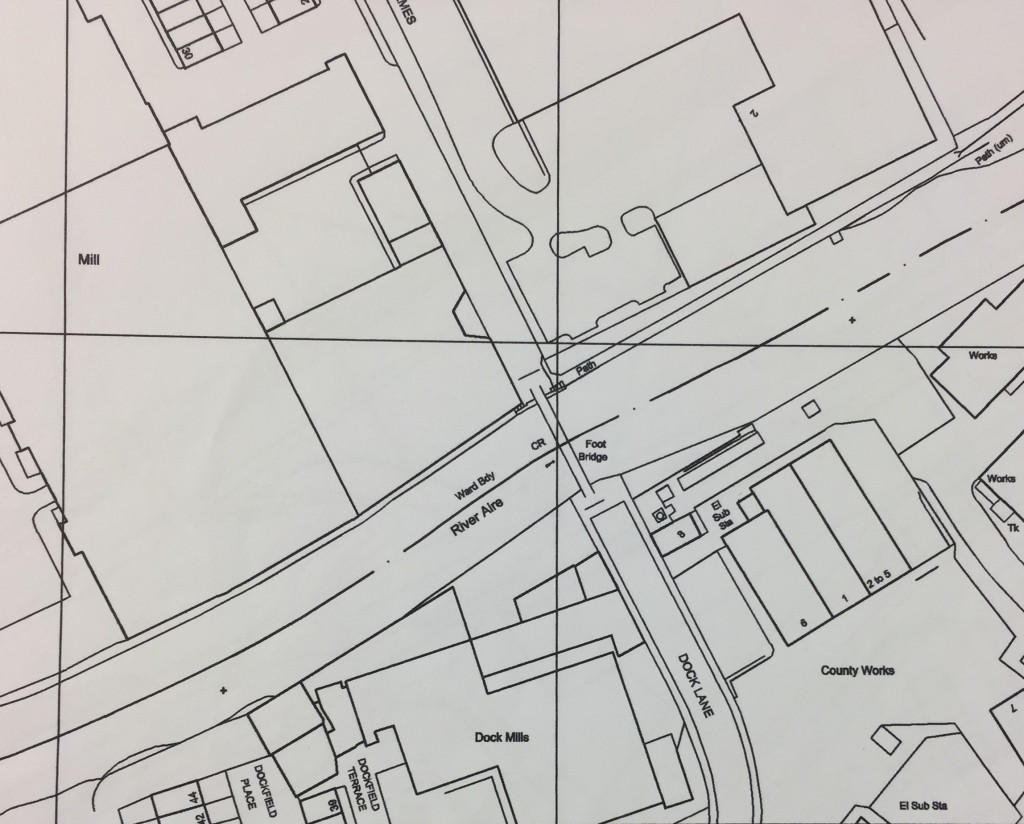

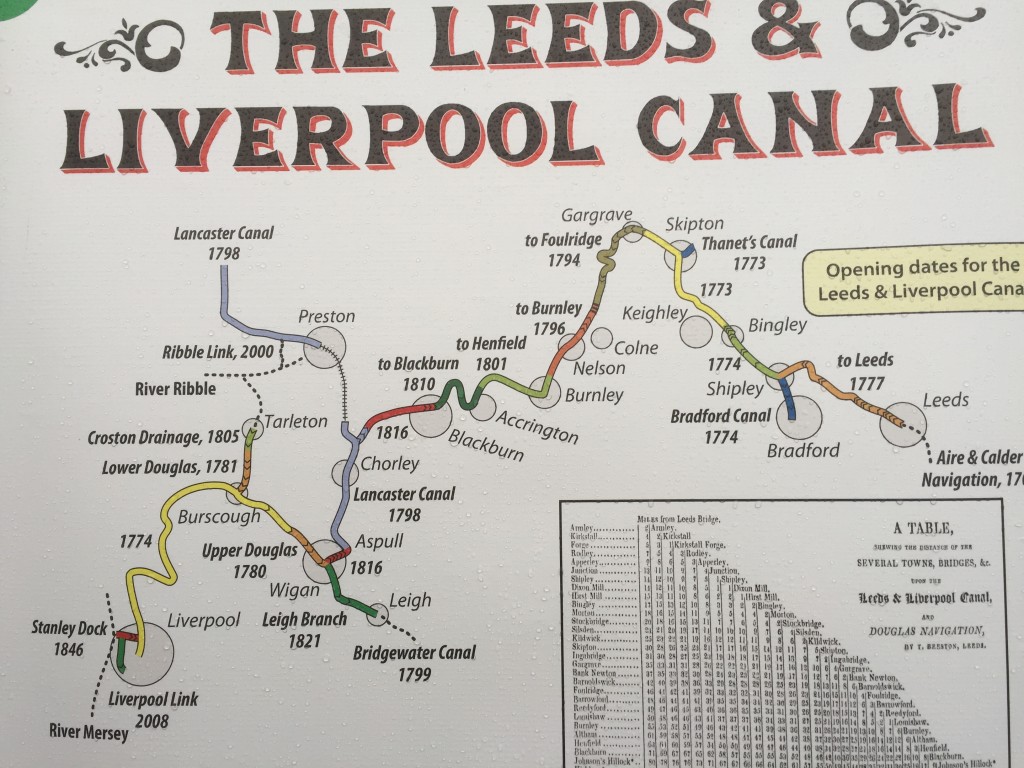

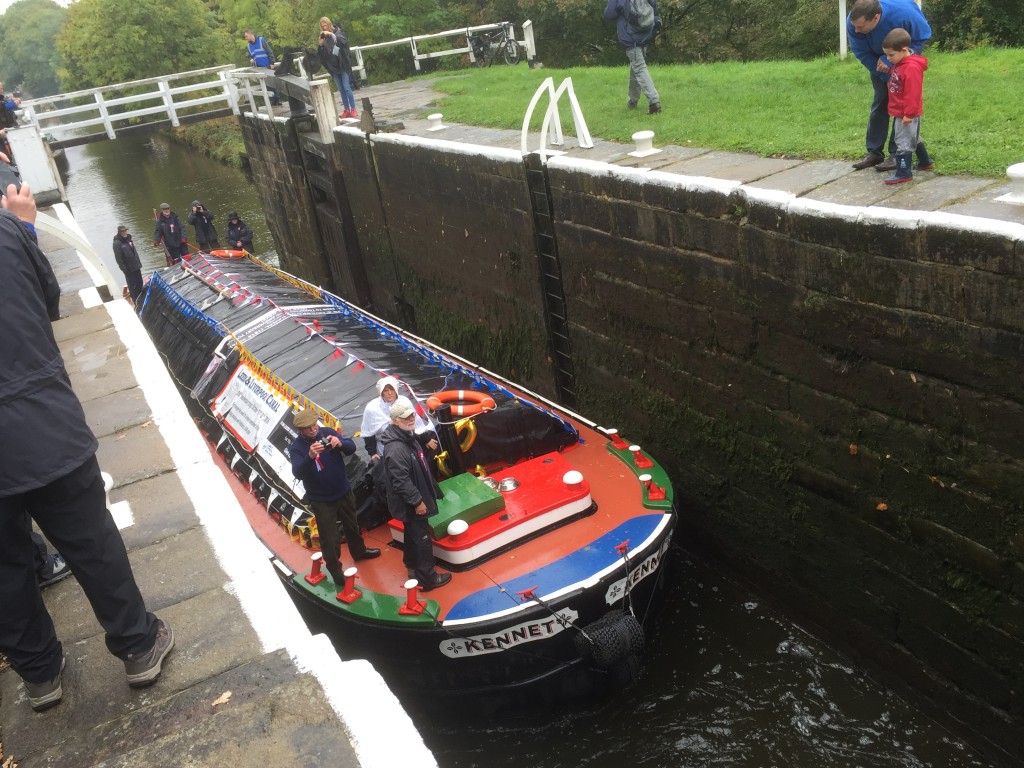

Maybe that’s too far back. Maybe I should begin in the 1770s, when the first sections of the Leeds to Liverpool canal were cut — through Shipley and Bingley — the first stage in a process that would connect Leeds, Bradford and Liverpool by water, and catalyse those cities’ rapid expansion during the Industrial Revolution.

Maybe that’s too far back. Maybe I should begin in the 1770s, when the first sections of the Leeds to Liverpool canal were cut — through Shipley and Bingley — the first stage in a process that would connect Leeds, Bradford and Liverpool by water, and catalyse those cities’ rapid expansion during the Industrial Revolution.

Or maybe I should just begin last month, when the Leeds-based arts collective Invisible Flock (with whom I have enjoyed some productive dialogues over recent years) invited me to attend the launch evening of their new, Liverpool-based installation, Aurora. Which is why, last night, I found myself walking through pouring rain in the Toxteth area of Liverpool, along with other intrepid visitors to Aurora‘s very first public showing. Everyone was cold and damp, and we’d been warned that we were likely to stay cold and damp, because we were about to step inside a reservoir. Toxteth Reservoir, that is: a remarkable, Grade-2 listed building that is part of Liverpool’s industrial heritage.

Which is why, last night, I found myself walking through pouring rain in the Toxteth area of Liverpool, along with other intrepid visitors to Aurora‘s very first public showing. Everyone was cold and damp, and we’d been warned that we were likely to stay cold and damp, because we were about to step inside a reservoir. Toxteth Reservoir, that is: a remarkable, Grade-2 listed building that is part of Liverpool’s industrial heritage.

Those forbidding, sloping walls, built around 1845, were designed to contain and support vast quantities of water. This water, which presumably fell from the sky to begin with? — this being Liverpool — was held in a rectangular tank measuring around 2600 square metres. It was distributed as needed to provide clean water to the city’s rapidly expanding population, and also supplied early fire-fighting efforts, etc.

Those forbidding, sloping walls, built around 1845, were designed to contain and support vast quantities of water. This water, which presumably fell from the sky to begin with? — this being Liverpool — was held in a rectangular tank measuring around 2600 square metres. It was distributed as needed to provide clean water to the city’s rapidly expanding population, and also supplied early fire-fighting efforts, etc.

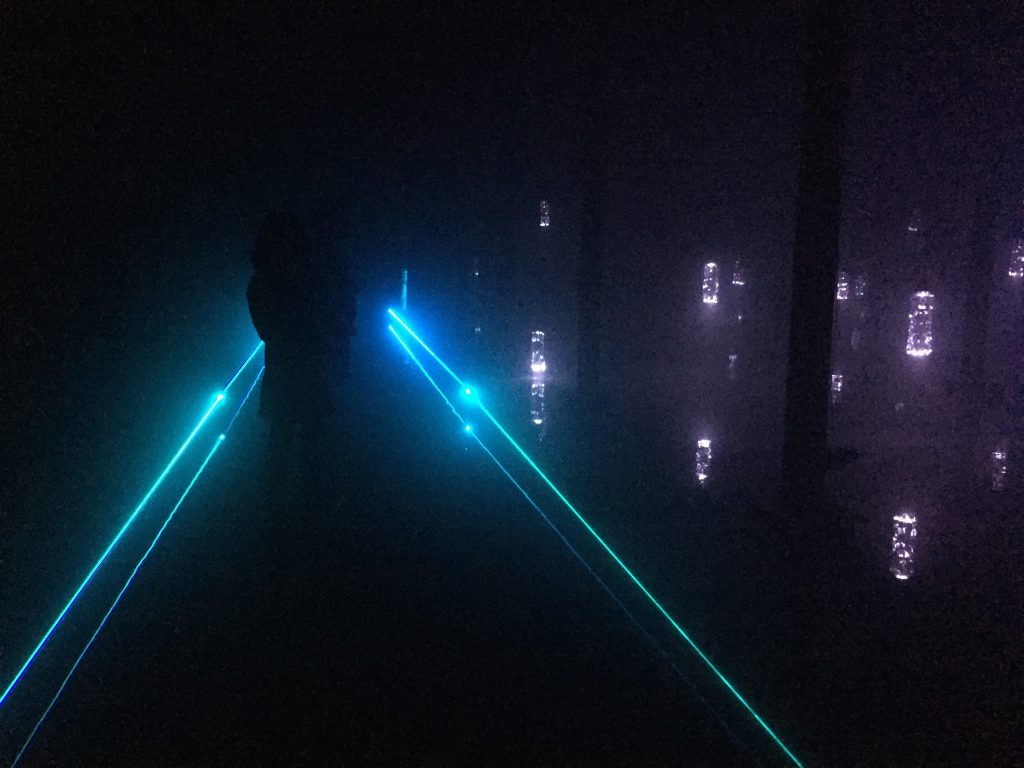

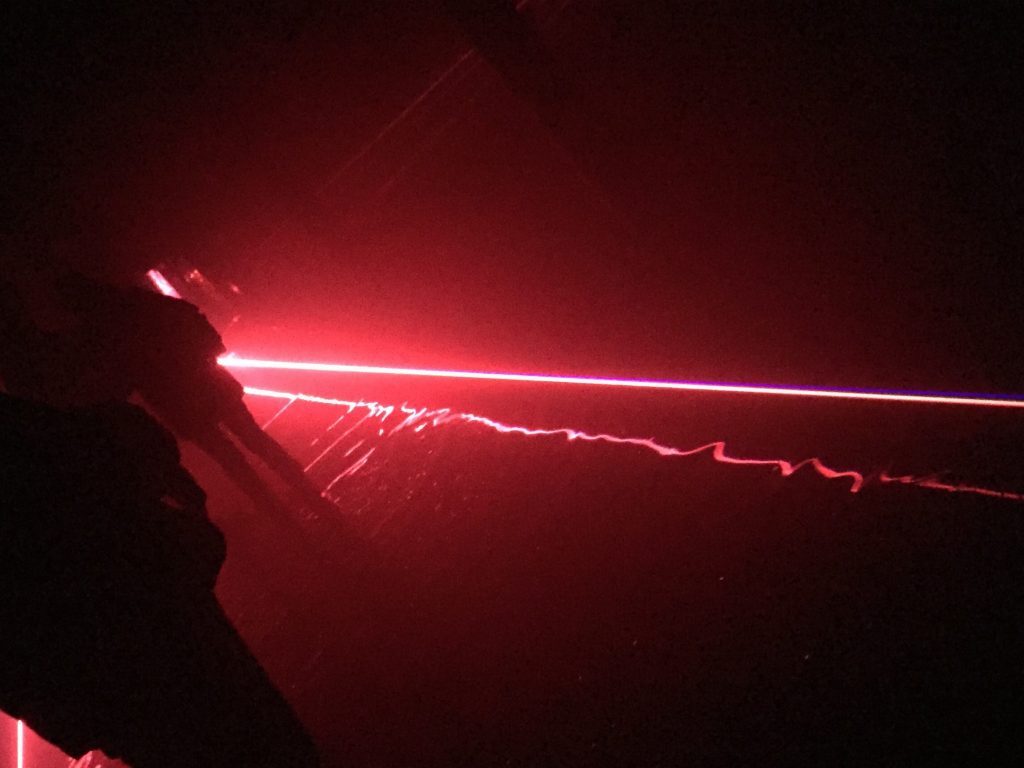

The roof of this vast space is held up with rows of iron pillars. Moving inside the building, we found ourselves navigating our way freely around a big rectangle of walkways, shadowing the interior edges of the building, which were marked out by coloured lasers. These walkways were all under 2 or 3 centimetres of water, so as we walked, patterns of coloured light rippled out in front of us.

The roof of this vast space is held up with rows of iron pillars. Moving inside the building, we found ourselves navigating our way freely around a big rectangle of walkways, shadowing the interior edges of the building, which were marked out by coloured lasers. These walkways were all under 2 or 3 centimetres of water, so as we walked, patterns of coloured light rippled out in front of us.

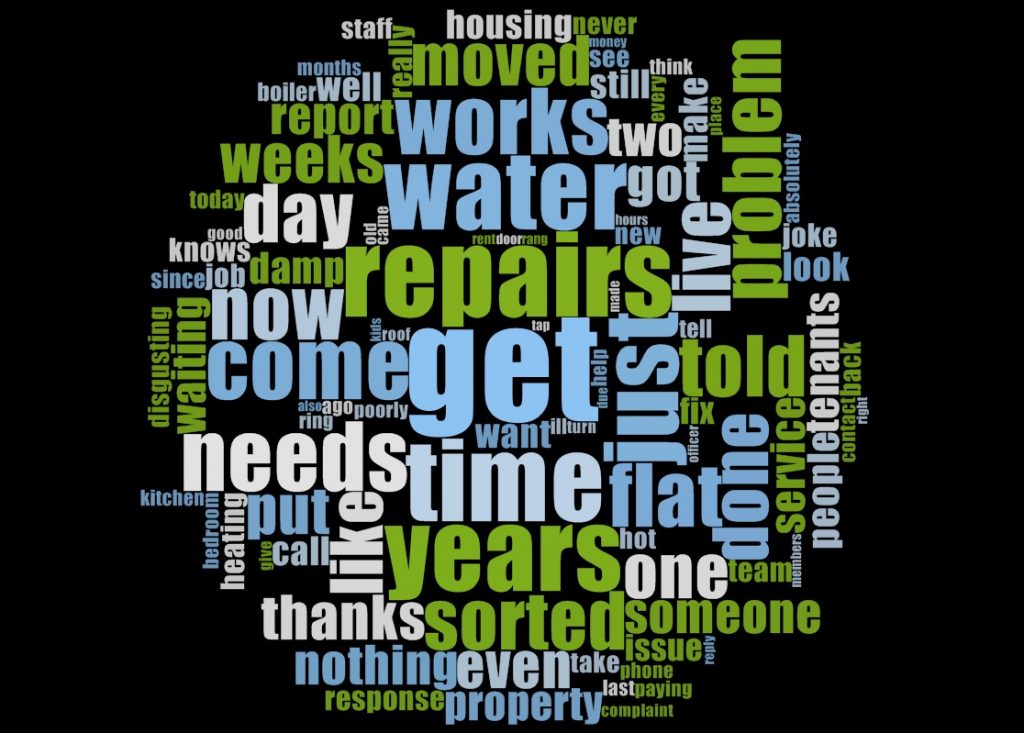

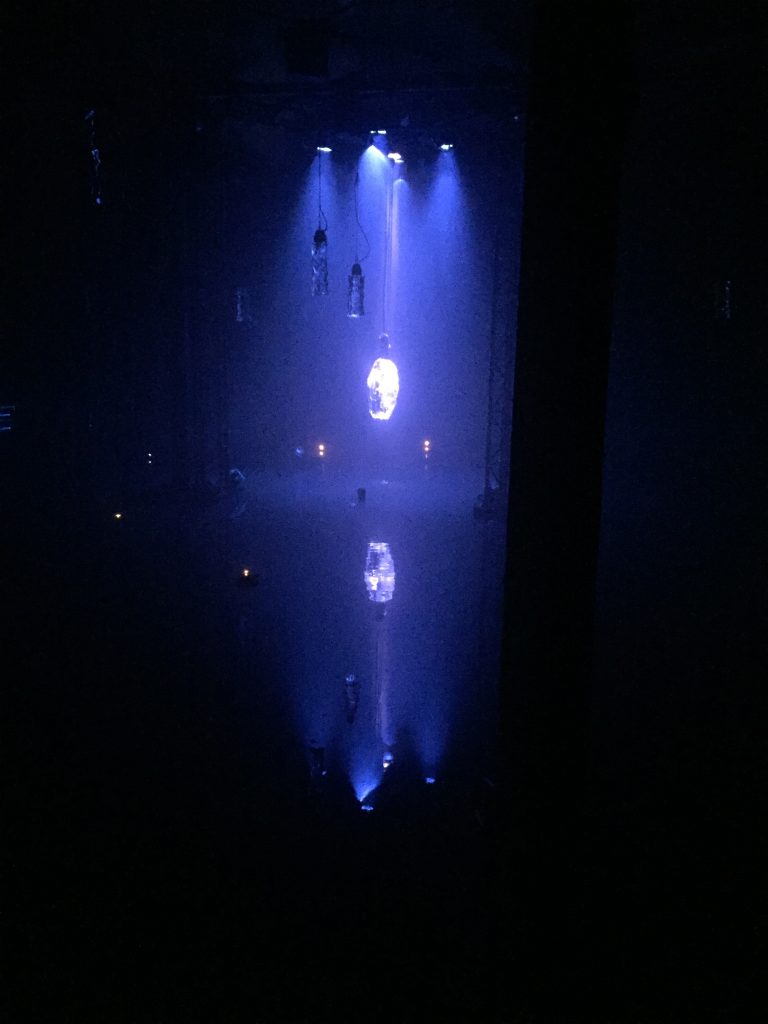

I went into Aurora not really knowing what to expect. The last piece of Invisible Flock’s that I saw, Control, was a theatre show based on interviews with a myriad of “experts” — which explored who has what degree of control over the way the world is heading just now (politically, environmentally, technologically…). Control was all about the language from these interviews — words, words, words — and so I was expecting that to be continued somehow in Aurora. But instead… no words at all. Just impenetrable darkness, a void without clear edges, and water lapping around our feet, moisture clinging to us in the dank atmosphere. And light. Let there be light, said Invisible Flock. And behold, there was light. Especially, centrally, light picking out a big lump of slowly melting ice — hanging suspended in the middle of the space, and reflecting in the water below. Sometimes the ice was visible. Sometimes not.

I went into Aurora not really knowing what to expect. The last piece of Invisible Flock’s that I saw, Control, was a theatre show based on interviews with a myriad of “experts” — which explored who has what degree of control over the way the world is heading just now (politically, environmentally, technologically…). Control was all about the language from these interviews — words, words, words — and so I was expecting that to be continued somehow in Aurora. But instead… no words at all. Just impenetrable darkness, a void without clear edges, and water lapping around our feet, moisture clinging to us in the dank atmosphere. And light. Let there be light, said Invisible Flock. And behold, there was light. Especially, centrally, light picking out a big lump of slowly melting ice — hanging suspended in the middle of the space, and reflecting in the water below. Sometimes the ice was visible. Sometimes not.

As an experience, Aurora runs for about 40 minutes. Which is actually quite a long time when you’re standing in the dark and the cold, watching light play across water. If this were a regular gallery installation, it would be the kind of thing you’d just walk in and out of, when you’ve had enough, but here — like a theatre show — we all entered together and left together at the end. A captive audience. Trapped in the dark. Not quite sure how to get out even if you wanted to. So you’re very much left alone with your own thoughts. Partly because talking would seem, somehow, wrong in here. And partly because the sound score — an eerie combination of electronics and strings — is sometimes so loud it would drown out speech. Although it’s also sometimes so quiet that you can hear water dripping.

As an experience, Aurora runs for about 40 minutes. Which is actually quite a long time when you’re standing in the dark and the cold, watching light play across water. If this were a regular gallery installation, it would be the kind of thing you’d just walk in and out of, when you’ve had enough, but here — like a theatre show — we all entered together and left together at the end. A captive audience. Trapped in the dark. Not quite sure how to get out even if you wanted to. So you’re very much left alone with your own thoughts. Partly because talking would seem, somehow, wrong in here. And partly because the sound score — an eerie combination of electronics and strings — is sometimes so loud it would drown out speech. Although it’s also sometimes so quiet that you can hear water dripping. A lot of things run through your head in a situation like this. I went through a phase, for example, of rejection and denial. It’s really just a big son et lumiere display, I thought to myself for a while. Where is the content? I’d read that this was some kind of local community project, so where was the community — other than standing around with me in the dark? I’d also read that this was to be a piece about global “water issues” like flooding and drought… but how can sound and light alone talk about those concerns?

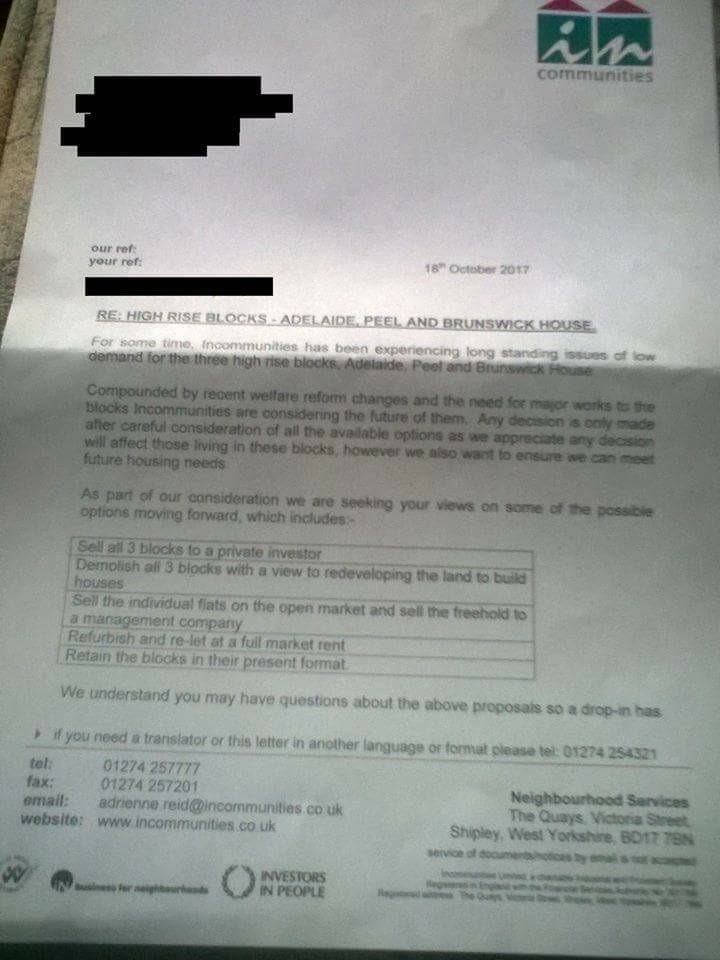

A lot of things run through your head in a situation like this. I went through a phase, for example, of rejection and denial. It’s really just a big son et lumiere display, I thought to myself for a while. Where is the content? I’d read that this was some kind of local community project, so where was the community — other than standing around with me in the dark? I’d also read that this was to be a piece about global “water issues” like flooding and drought… but how can sound and light alone talk about those concerns? There was a stage in the show when we started to be shown more of the looming, arch-like architecture of the building — and though you can’t really see it in the picture above, it actually starting raining inside the building, around the inside of the exterior wall. This was the point when the piece felt the most “human” to me — an evocation both of man-made structures and of the weather we all live with in the north of England… the weather that Liverpool’s Victorian workers trudged through, just as we had today.

There was a stage in the show when we started to be shown more of the looming, arch-like architecture of the building — and though you can’t really see it in the picture above, it actually starting raining inside the building, around the inside of the exterior wall. This was the point when the piece felt the most “human” to me — an evocation both of man-made structures and of the weather we all live with in the north of England… the weather that Liverpool’s Victorian workers trudged through, just as we had today.

But what was most surprising, and most chilling perhaps, was just how inhuman, or rather nonhuman, Aurora turned out to be. To speak of flooding or drought is to speak, really, of the impacts on humans of there being too much water, or too little, for our accustomed ways of living. But in the end, Aurora seemed to me spectacularly unconcerned with such passing concerns. It really was about water as water. Mysterious. Impenetrable (even when we dive headfirst into it). Eternal. We’re made of it, we depend on it, but it does not need us.

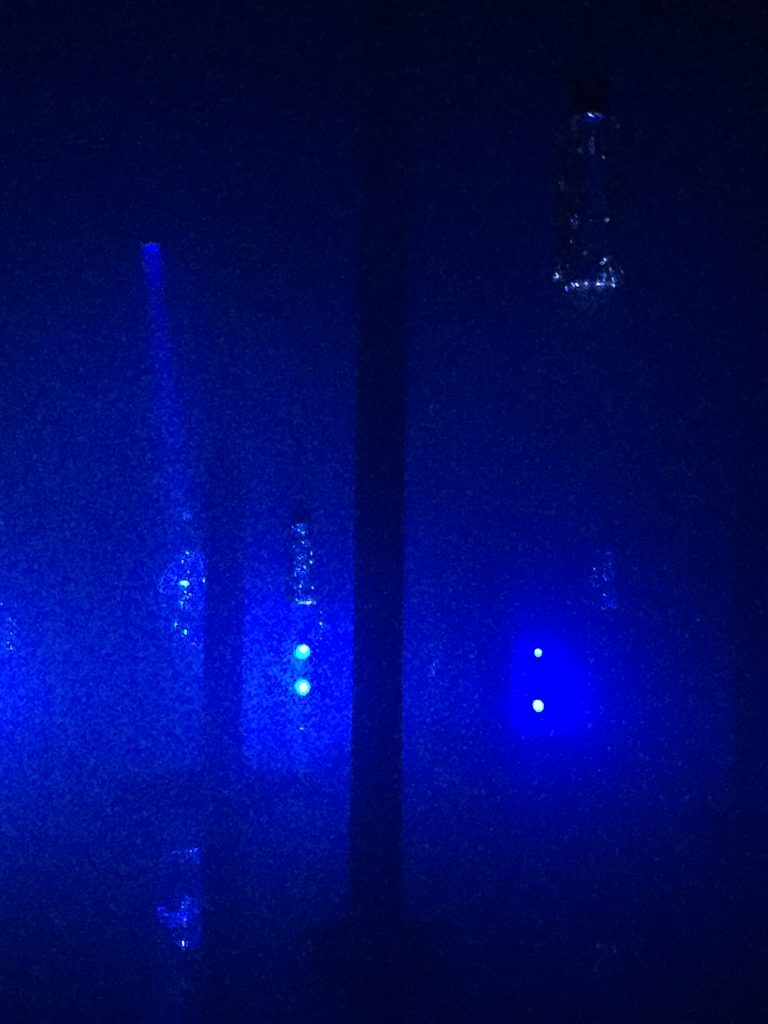

For me, this thought was epitomised by the strange, hanging shapes that formed a kind of field, or cloud, or constellation around that central ice block. Shapes that looked at first like lanterns, then maybe water containers of some sort… but also weirdly alien. It crossed my mind, briefly, that they were the eggs of an Alien hive mother… Eventually I realised that they too, like the egg-like form in the centre, were ice. And they were melting. Water going from solid to liquid.

For me, this thought was epitomised by the strange, hanging shapes that formed a kind of field, or cloud, or constellation around that central ice block. Shapes that looked at first like lanterns, then maybe water containers of some sort… but also weirdly alien. It crossed my mind, briefly, that they were the eggs of an Alien hive mother… Eventually I realised that they too, like the egg-like form in the centre, were ice. And they were melting. Water going from solid to liquid.

In one particularly eerie moment, these shapes hung very low over the water — as if threatening to descend right into it — before rising back up into the “stars”. The music during this whole section seemed mournful, haunting — I can’t even start to describe it — but in my mind the whole thing started to crystallise as a piece that was really, truly indifferent to human beings. Like the planet itself, perhaps. The planet that we are irrevocably altering with our own indifference towards it. The glaciers are melting. Sea levels are rising. The next Great Extinction of earthly species is already underway, and we started it — round about the time of the Industrial Revolution, when this building went up and we started burning fossil fuels at an ever-more-exponential rate. Aurora, then, evokes the facts of a very Dark Ecology. . . . But the oceans will outlast us. And so, in the end, will the ice.

In one particularly eerie moment, these shapes hung very low over the water — as if threatening to descend right into it — before rising back up into the “stars”. The music during this whole section seemed mournful, haunting — I can’t even start to describe it — but in my mind the whole thing started to crystallise as a piece that was really, truly indifferent to human beings. Like the planet itself, perhaps. The planet that we are irrevocably altering with our own indifference towards it. The glaciers are melting. Sea levels are rising. The next Great Extinction of earthly species is already underway, and we started it — round about the time of the Industrial Revolution, when this building went up and we started burning fossil fuels at an ever-more-exponential rate. Aurora, then, evokes the facts of a very Dark Ecology. . . . But the oceans will outlast us. And so, in the end, will the ice.

Towards the end of the piece, sharp shafts of laser light begin to stab their way into the middle of the space — as if from the outer edges of outer space. And then, before you know it, those beams are catching and refracting through the hanging icicles, and the music goes from somber to strangely joyful, and there’s a dazzling symphony — or choreography, or something — of co-ordinated light and sound.

Towards the end of the piece, sharp shafts of laser light begin to stab their way into the middle of the space — as if from the outer edges of outer space. And then, before you know it, those beams are catching and refracting through the hanging icicles, and the music goes from somber to strangely joyful, and there’s a dazzling symphony — or choreography, or something — of co-ordinated light and sound. Perhaps this, finally, is the aurora borealis evoked by the piece’s title. The Northern Lights. The spectacular natural light show that’s visible in areas approaching the north pole. (Come to that, it could equally well be the aurora australis – the Southern Lights. Both the ice-caps are melting, after all.) For me, though, something about those lights beaming in from outer space made it something else again…. A picture, perhaps, of an ocean-covered earth echoing with the music of the spheres — catching the starshine arriving from light years away, and amplifying its harmonies. An earth no longer despoiled by humans, but restored to one-ness with the rest of the universe…?

Perhaps this, finally, is the aurora borealis evoked by the piece’s title. The Northern Lights. The spectacular natural light show that’s visible in areas approaching the north pole. (Come to that, it could equally well be the aurora australis – the Southern Lights. Both the ice-caps are melting, after all.) For me, though, something about those lights beaming in from outer space made it something else again…. A picture, perhaps, of an ocean-covered earth echoing with the music of the spheres — catching the starshine arriving from light years away, and amplifying its harmonies. An earth no longer despoiled by humans, but restored to one-ness with the rest of the universe…?

… Or something like that, anyway. Afterwards, I found two phrases from very different songs echoing around my head. From Canadian singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn, the chorus of his hymn-like 1979 song “Hills of Morning“:

… Or something like that, anyway. Afterwards, I found two phrases from very different songs echoing around my head. From Canadian singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn, the chorus of his hymn-like 1979 song “Hills of Morning“:

Let me be a little of your breath

Moving over the face of the deep —

I want to be a particle of your light

Flowing over the hills of morning

Or on a bleaker, perhaps more realistic note, some words from U2’s 2014 song “Iris” — a song of lament for the mother Bono lost when he was a child:

The stars are bright but do they know

The universe is beautiful … but cold.

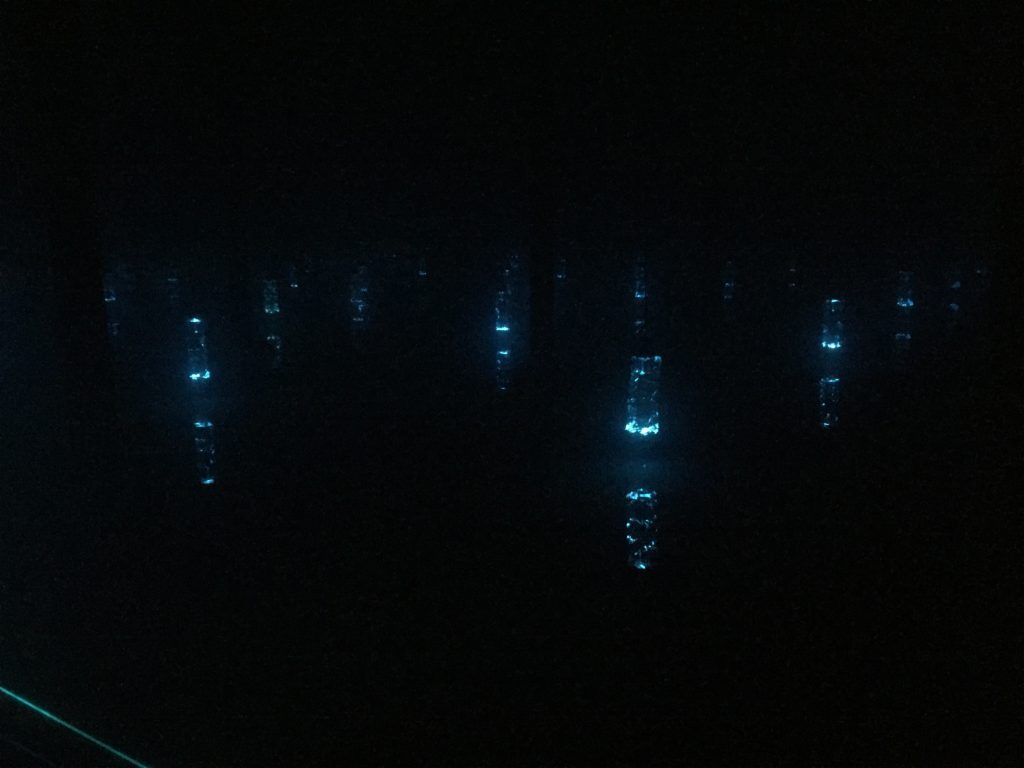

Having reached its climax, Aurora ends, and mysterious ice blocks appear lit at the corners of the walkways, to help light our way out. Ice blocks with items frozen inside them… is this an arrow? a quill? …human relics of a forgotten civilization, preserved in ice forever.

Having reached its climax, Aurora ends, and mysterious ice blocks appear lit at the corners of the walkways, to help light our way out. Ice blocks with items frozen inside them… is this an arrow? a quill? …human relics of a forgotten civilization, preserved in ice forever.

But then, bit by bit, the magic ebbs away. On the way out, we can suddenly see the ramp up to the flooded walkways (when we came in, it was too dark…). Those familiar white lines marking the perimeters of a stage space or holding area. Suddenly so banal after the mysteries of what we just witnessed. But then that’s the way of magic, isn’t it? Sometimes its most magical when you can see how they pulled off the trick…

But then, bit by bit, the magic ebbs away. On the way out, we can suddenly see the ramp up to the flooded walkways (when we came in, it was too dark…). Those familiar white lines marking the perimeters of a stage space or holding area. Suddenly so banal after the mysteries of what we just witnessed. But then that’s the way of magic, isn’t it? Sometimes its most magical when you can see how they pulled off the trick…

And outside, it’s still raining. It’s still Liverpool. And those walls that had seemed so imposing and forbidding when we went in seem suddenly much smaller, more ordinary… But ordinary like the outside of the Doctor’s Tardis. Because a moment ago they contained the universe inside…

And outside, it’s still raining. It’s still Liverpool. And those walls that had seemed so imposing and forbidding when we went in seem suddenly much smaller, more ordinary… But ordinary like the outside of the Doctor’s Tardis. Because a moment ago they contained the universe inside… And so we repair to the launch reception for Aurora. Just up the street, on the other side of the Catholic Church, is the Mount Carmel Social Club… a community venue where members of the local community mix in with the slightly incongruous arty-types who seem to be staffing the show. Once everyone has a drink, the absence of words during the performance itself is (over-)compensated for by an excess of words from the great and the good — the Arts Council, the City of Liverpool, the commissioning body FACT, etc. It’s all the usual corporate verbiage that you get on such occasions, but it’s even harder to listen to than usual after what we just witnessed. Representing Invisible Flock, though, Victoria Pratt is refreshingly brief in her comments. She prefers, I think, to let the work speak for itself.

And so we repair to the launch reception for Aurora. Just up the street, on the other side of the Catholic Church, is the Mount Carmel Social Club… a community venue where members of the local community mix in with the slightly incongruous arty-types who seem to be staffing the show. Once everyone has a drink, the absence of words during the performance itself is (over-)compensated for by an excess of words from the great and the good — the Arts Council, the City of Liverpool, the commissioning body FACT, etc. It’s all the usual corporate verbiage that you get on such occasions, but it’s even harder to listen to than usual after what we just witnessed. Representing Invisible Flock, though, Victoria Pratt is refreshingly brief in her comments. She prefers, I think, to let the work speak for itself.