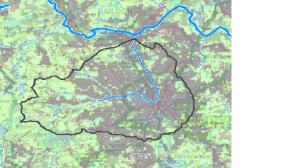

Today I went on a bit of a scouting adventure… Not in the Shipley area, this time, but out to the West of Bradford, in the vicinity of Chellow Dean Beck and Pitty Beck, two of the main tributaries that flow in to help form Bradford Beck before it flows underground and through the city centre. (They’re the two wiggly bits coming in from the north of the main arm of the Beck in the diagram below, prior to the Beck turning that big corner in the city and going north to Shipley and the Aire.)

Anyway, I was scouting out these tributaries, prior to leading some primary school children on field trips along them. This is part of their project work on water and local rivers, which we’re hoping will provide the basis for a performance for the Mirror Pool in Bradford’s City Centre on May 13th (a follow-on, of sorts, from last year’s performances in Shipley). Since the Mirror Pool is a site in which one can frequently see kids splashing around (OK, maybe not at this time of year!), it seemed logical to work with schools to make something for it. This is in response to Bradford Council’s request that we make a performance for the Mirror Pool to mark the opening of the Europe-wide Flood Resilient Cities conference.

The collaborating schools are Crossley Hall Primary and St. James’ Church Primary, which are located close by to Chellow Dean Beck and Pitty Beck, respectively. And what both tributaries have in common are wetland areas that were put in by the Council from 2004, including special reed ponds. These are, apparently, an experiment in treating water quality: according to Tony Poole (Chief Drainage Engineer at the Council), the reeds and their soils have a natural cleaning/filtering effect on water that may already have been contaminated upstream by human impacts. What I hadn’t gathered from talking to Tony, however, was just how different these similar wetland projects appear in practice…

Here’s the treatment pools in the Chellow Dean wetlands (covered with some snow and ice first thing this morning), with the Beck flowing on to the right, and the reed ponds in the background… Like the whole wetland area, the landscaping is neat and appealing despite the oddly geometric ponds, and the reeds grow high in their neatly defined beds…

Here’s the treatment pools in the Chellow Dean wetlands (covered with some snow and ice first thing this morning), with the Beck flowing on to the right, and the reed ponds in the background… Like the whole wetland area, the landscaping is neat and appealing despite the oddly geometric ponds, and the reeds grow high in their neatly defined beds…

There’s a sense, from the whole spirit of the place, of the community here taking pride in this slightly incongruous bit of ecological intervention… That impression is thrown into sharp relief by the comparative state of the Pitty Beck wetland area…

There’s a sense, from the whole spirit of the place, of the community here taking pride in this slightly incongruous bit of ecological intervention… That impression is thrown into sharp relief by the comparative state of the Pitty Beck wetland area…

The whole area feels neglected, scrubby… even the ponds look poorly maintained and manicured by comparison with Chellow Dean. The reed ponds (in the background of the shot above) have a lot of rubbish in them too…

The whole area feels neglected, scrubby… even the ponds look poorly maintained and manicured by comparison with Chellow Dean. The reed ponds (in the background of the shot above) have a lot of rubbish in them too…

Tony Poole had mentioned to me that there are less people living around the Pitty Beck wetland, and thus less of a sense of community ‘ownership’ and collaboration in keeping the area up. But there are in fact quite a few houses not far from here, and I saw people walking dogs etc. My impression, though, was that this area was generally more run-down and disadvantaged than the area around Chellow Dean, and that the Council has perhaps not done enough to engage and involve them in the area’s upkeep (let alone keep up the area themselves!). It surely can’t help when local residents are confronted with signs like this at the entrances to the wetland area:

Tony Poole had mentioned to me that there are less people living around the Pitty Beck wetland, and thus less of a sense of community ‘ownership’ and collaboration in keeping the area up. But there are in fact quite a few houses not far from here, and I saw people walking dogs etc. My impression, though, was that this area was generally more run-down and disadvantaged than the area around Chellow Dean, and that the Council has perhaps not done enough to engage and involve them in the area’s upkeep (let alone keep up the area themselves!). It surely can’t help when local residents are confronted with signs like this at the entrances to the wetland area:

No doubt the sign is up for legal reasons (to prevent a “right of way” establishing itself by default, through what they call “custom and practice”), but the wording is unwelcoming, to say the least. Little wonder, perhaps, that at least one of the locals has responded rudely:

No doubt the sign is up for legal reasons (to prevent a “right of way” establishing itself by default, through what they call “custom and practice”), but the wording is unwelcoming, to say the least. Little wonder, perhaps, that at least one of the locals has responded rudely:

If you can’t quite make it out, that’s the word “DICKHEADS” scrawled across the map explaining the purpose of the wetland area… And in the photo below, you can see where Pitty Beck gets sucked into a huge, unsightly bit of piping that takes it underneath the main Thornton Road just to the south (the road visible on the graffiti-ed map above!).

If you can’t quite make it out, that’s the word “DICKHEADS” scrawled across the map explaining the purpose of the wetland area… And in the photo below, you can see where Pitty Beck gets sucked into a huge, unsightly bit of piping that takes it underneath the main Thornton Road just to the south (the road visible on the graffiti-ed map above!).

Crossing over the main road, in search of the Beck’s continuation, I was confronted rather abruptly with a long line of high fencing and walls, and a notice that leaves you in no doubt that you’re not welcome…

Crossing over the main road, in search of the Beck’s continuation, I was confronted rather abruptly with a long line of high fencing and walls, and a notice that leaves you in no doubt that you’re not welcome…

Here, it seems, the Beck flows into private land – the Stone Heights property development (est. 1999) with its perfectly manicured gardens, tennis court, and elevated summer house that looks uncomfortably like a watchtower…

Here, it seems, the Beck flows into private land – the Stone Heights property development (est. 1999) with its perfectly manicured gardens, tennis court, and elevated summer house that looks uncomfortably like a watchtower…

As may be apparent from this picture, I chose to disregard the “No Trespassing” signs in order to see if I could get closer to the river (because trespassing is not actually an offence unless you break something, and because I firmly believe that watercourses belong to everybody, property laws be damned!). The river is at the bottom of the valley in the shot above, below the high wall buttressing the road… Shortly after taking this picture I was politely ushered off the property by a gardener who explained that the owners are “a bit funny” about uninvited visitors… And that no, they probably would not be responsive to a request to bring some schoolchildren on a visit…

As may be apparent from this picture, I chose to disregard the “No Trespassing” signs in order to see if I could get closer to the river (because trespassing is not actually an offence unless you break something, and because I firmly believe that watercourses belong to everybody, property laws be damned!). The river is at the bottom of the valley in the shot above, below the high wall buttressing the road… Shortly after taking this picture I was politely ushered off the property by a gardener who explained that the owners are “a bit funny” about uninvited visitors… And that no, they probably would not be responsive to a request to bring some schoolchildren on a visit…

My experience attempting to walk along Chellow Dean Beck had been very different. There’s a pleasant valley walk up through the wetland area, as the river weaves and bends its way through the soft ground…

No sense of feeling unwelcome here. And there’s evidence of playful, personal interventions in the landscape – such as the little guitar-playing frog and improvised treehouse below…

No sense of feeling unwelcome here. And there’s evidence of playful, personal interventions in the landscape – such as the little guitar-playing frog and improvised treehouse below…

If you track Chellow Dean far enough upstream, under another main road and up through an open field, you eventually get to the gorgeous surroundings of the twin Victorian reservoirs, full of bird life and a haven for dog-walkers…

If you track Chellow Dean far enough upstream, under another main road and up through an open field, you eventually get to the gorgeous surroundings of the twin Victorian reservoirs, full of bird life and a haven for dog-walkers…

The reservoirs no longer serve any utilitarian purpose: it was long since concluded that Chellow Dean Beck has little enough water in it without the Council siphoning it off (presumably to serve the wool industry and its dye-houses, back in the day…). But it’s all maintained beautifully as a park area. I also was also personally pleased to see the domed Victorian pumping station at the base of the lower reservoir, very similar to the ones next to the Aire to the west of Shipley.

The reservoirs no longer serve any utilitarian purpose: it was long since concluded that Chellow Dean Beck has little enough water in it without the Council siphoning it off (presumably to serve the wool industry and its dye-houses, back in the day…). But it’s all maintained beautifully as a park area. I also was also personally pleased to see the domed Victorian pumping station at the base of the lower reservoir, very similar to the ones next to the Aire to the west of Shipley.

The field trips for the two school groups, then, are going to be rather different. The Crossley Hall children have been doing project work on ‘the Victorians’ so maybe we’ll hike them up as far as the reservoir (the teacher’s suggestion), and take in the views… Lovely. The children at St. James’s have an altogether less appealing walk to enjoy, but we shall see what they make of it. Better turn my mind to thinking how to engage them!

The field trips for the two school groups, then, are going to be rather different. The Crossley Hall children have been doing project work on ‘the Victorians’ so maybe we’ll hike them up as far as the reservoir (the teacher’s suggestion), and take in the views… Lovely. The children at St. James’s have an altogether less appealing walk to enjoy, but we shall see what they make of it. Better turn my mind to thinking how to engage them!

After reading this article I feel I must comment with regard to The Pitty Beck wetlands. I definitely agree with all that has been said about the condition of the wetlands, but most say that several of the local residents in close proximity to the wetlands along with the area community centre committee have over the last several years been trying to get the local council to keep up with the upkeep of the wetlands ( which we were originally told they would be doing) unfortunately we keep hitting a very large hurdle mainly a department within the Bradford Council by the name of asset management which seems to be avoiding anything to do with pitty beck or it’s surrounding areas. We are very found of our wetlands and do try to keep up with the littering etc but unfortunately we are a minority and with the large schools close by its very difficult.

What was wetlands originally? What is the long term history of it please

Well that all depends on your definition of wetlands, really. Any low-lying area that water flows to/through, and which humans haven’t modified, can tend towards becoming marshy – especially during periods of heavy rainfall. Traditionally we drain wet land (as opposed to wetlands) in order to make it usable for agriculture or building projects: trickling downhill flows of water will get channelled into underground pipes etc, to that the land itself remains drier. But if humans choose to *designate* a given area as a wetland, then some kind of reverse-engineering takes place to restore moisture to the land (e.g. digging ponds instead of just letting grass get puddled and muddy…). I don’t know if these remarks are helpful, Graham, but I’m afraid I don’t have the long term history of these areas to hand, and it’s 5 years since I wrote the blog you’re commenting on…